When the diversity diversifies

“Immigration to the Nordic region does not only mean more diversity. What we’re seeing now is that the diversity is diversifying. We get super-diversity,” says Tuomas Martikainen, Director of the Finnish Institute of Migration.

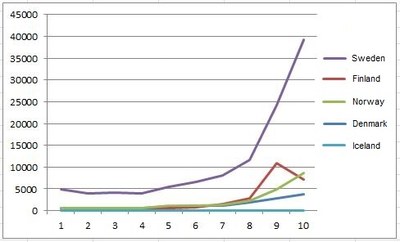

The number of asylum seekers arriving to the Nordic countries in 2015 was more than twice that of 2014. A total of 248,077 asylum seekers arrived last year. Until October all graphs pointed steeply upward in all the Nordic countries except for Finland, which had already started tightening the rules:

Asylum seekers to the Nordic countries Jan-Oct 2015

Major refugee flows have been seen before, like during the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Yet according to Tuomas Martikainen today’s refugee flows are different. This is partly down to technology, which makes it easier to move from one country to another and which allows refugees to make quick decisions based on information found on social media.

Then there is the sheer number of refugees.

“There are already more than 150,000 Iraqis in the Nordic countries. That is more than the number of Finns living in Sweden,” Tuomas Martikainen told the conference ‘How are you doing in the Nordic countries?’ in Turku.

Iraqis are already the second largest immigration group in Sweden. The number in Iraqis in Denmark and Finland is also considerable, making them the fourth largest immigrant group in those countries.

“Meanwhile we still entertain old ideas when it comes to how we group different people. We think a person coming from country A must belong to culture B and practice religion C.

“But people are influenced by the social setting they live in. They change and new links emerge. The resulting diversity is not the same that came in to the country.”

As an academic he has studied how people’s religion is influenced by their new country. The Institute of Migration is Finland’s only research institute specialising on migration research.

“Muslims in Turku, Vietnamese Buddhists, Iraqi Christian Chaldeans, the Lutheran Ingrian Finns and the Russian Orthodox Christians who live here are not practicing their religion in the same way as they did when they left their countries. The differences are sometimes very big.

“Take an example from a different country. We all have an idea of what Buddhism is and think about monks living in temples. But in the USA there are Buddhists practising their religion in buildings looking like churches, singing Buddhist psalms while sitting on benches

“None of that happened where they came from.”

Hot political potato

The flow of asylum seekers arriving in Europe and to the Nordic countries towards the end of last year became a hot political potato. No political coordination was achieved on a European or a Nordic level. Some countries, like Germany and Sweden, accepted a disproportionate share of the refugees. Thousands of asylum seekers arrived across borders which had not been used by refugees before, like the one between Norway and Russia.

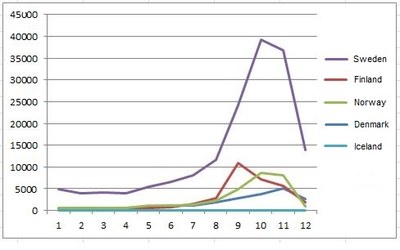

One after the other, European and Nordic countries introduced border controls or limited the access to social benefits and family reunifications. The result was a dramatic reduction in the number of refugees arriving:

Asylum seekers to the Nordic countries Jan-Dec 2015

There is still no end in sight for the Syrian civil war or other conflicts which cause people to flee. As national borders close, mental borders are being moved. Things are happening very fast.

“A year ago we could not have imagined that many would question whether the Schengen agreement on passport-free movement would survive,” says Tuomas Martikainen.

In Turku people speak 104 different languages. Five percent of the population speak Swedish, for historical reasons, while another five percent speak different languages.

Begin resembling the local population

“What research has taught us is that immigrants begin resembling the local population, and some people who have had to leave their country once are more likely to move again.

“Finland has one of the least urbanised populations in Europe. But if you look at the 450,000 people who moved from Karelia when the region became part of Russia, they were very much overrepresented during the major urbanisation of Finland which happened after the war.”

We still do not know how immigration will affect the Nordic countries, but in Finland you could already see ten years ago a new nationalism emerging though lion-themed jewellery and T-shirts reading ‘Thank you 1939-1945’ (Kiitos in Finnish). The message was to honour the war veterans.

“This tendency could be found even earlier among youths, 15 years ago."

Two paths

“The welfare state is facing major challenges. What will the future labour market look like and how will the economic basis for the welfare system work? We have an ageing population but also a changing population, where diversity means immigrants sometimes have different needs,” says Tuomas Martikainen.

Perhaps the most worrying aspect of the debate in Finland and other Nordic countries is what all this means for the social contract where we accept the role of the state. What happens if people loose faith in the way the state acts?

Tuomas envisages two different paths for Finland: The county will either arrive at a broader definition of ‘us’ and who are entitled to stay there, or it will develop a more narrow understanding which will raise the bar for how people are accepted into society.

- Asylum seekers to the Nordic countries

-

Country 2014 2015 Denmark 14792 21225 Finland 3620 32476 Iceland 176 354 Norway 11500 31145 Sweden 81180 162877 Total 111268 248077

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook