Towards a more authoritarian labour market – without freedom of expression?

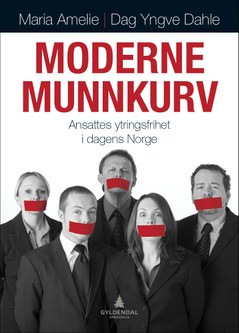

“This is not only about their working life. It is about their lives,” says Dag Yngve Dahle, who has written a book on the freedom of expression in working life together with Maria Amelie, called ‘Moderne munnkurv’, or Modern muzzle. They look at what happens to people who have been accused of a breach of loyalty to their employer.

The nine people are very different. Some, like Heidi Follet, knew there would be trouble when she published a cutting opinion piece about the The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration, NAV. Others, like ‘Mona’, were caught by surprise. She was summoned by the boss because of four words in an e-mail which she had sent to an angry government ministry employee to explain why no-one from Statoil’s leadership had attended a certain meeting.

Sometimes it is about whistleblowing. Like when an employee at Norway’s Radiation Protection Authority pointed out that the leadership had set the limits for a type of radioactive waste to half of what the International Atomic Energy Agency IAEA had recommended – in order to save more than 20 million kroner (€2.2m). In a different case, a security agency employee was sacked after fronting demands for a collective agreement.

The taboo of talking about the employer

“We see a pattern where employers do not take action if employees use their freedom of expression to post comments in social media or in opinion pieces about for instance immigration or religion. But reactions can be severe if employees pass comment on the company.”

Some of the most common reactions many receive, apart from a conversation with the boss under four eyes, is to be criticised in front of staff and to be excluded from the workplace community in various ways. Formal punishment can be the removal of certain tasks and the freezing of wages. Often the employer feel so bullied that he or she quits.

Dag Yngve Dahle and Maria Amelie describe how ‘Mona’ at Statoil reacted:

“In just a few days her existence had been turned upside-down. She had been considered a young and promising Statoil talent, but now she was labelled a disloyal traitor. She had used to start her day by drinking good quality coffee and listening to music on her way to work. Now she couldn’t face getting up in the morning. She just wanted to stay under her duvet. Facing reality made no sense. Thoughts about what had happened ran through her like gushing waves, they did not stop, they returned over and over again, they came with a gnawing doubt. Was it her, was something wrong with her?”

All she had done was to answer that she too “was surprised” by the fact that no-one from Statoil’s leadership had had time to attend the government ministry’s external meeting. She used the same expression as the author of the letter.

What state is Statoil’s generosity in?

“Is that the reason why they believe you have acted disloyally?” asked a surprised company doctor when she called Mona in to talk about why she had gone of sick.

The company doctor reported the affair as an “unjust, serious allegation” to the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority. Lawyers in Mona’s trade union agreed.

The authors ask what state Statoil’s generosity is in when the company cannot even tolerate a trifling matter like that? And does what happened represent the state of the Norwegian labour market?

“We have seen a Trumpification of the Norwegian labour market,” says Dag Yngve Dahle.

“We have seen a Trumpification of the Norwegian labour market,” says Dag Yngve Dahle.

“The relationship between the leader and the employees has changed. It’s ‘You are fired’ all over.”

Unpleasant methods

The authors commissioned a survey from the Norwegian Society of Engineers and Technologists, NITO, which asked members whether they themselves had experienced any sanctions as a result of things they had said or written. Nearly ten percent of the members answered yes, while nearly double that – 18.1 percent – said they knew someone at work who had experienced such sanctions.

“There are some rather unpleasant methods being used to reprimand people or push them out. This has probably been the case in the past, too. But we shouldn’t be surprised that people get problems, when you consider how much work means to many.”

In several cases employees developed depression, and some considered suicide. Dag Yngve Dahle believes this is linked to a major change in working life, where the old head of personnel, who often took the employees’ side, has been replaced by HRM leaders who support the leadership.

HRM, or Human Resource Management, is often divided into ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ HRM. The soft version focuses on employees’ engagement and motivation, striving for common values and cooperation. The hard version focuses on controlling, steering and punishing staff in order to make sure they do a good job.

Hard HRM in the oil industry

“In Norway the hard HRM model has partly been imported by the oil industry, but it has also been used by companies like Telenor and by public services like NAV.”

But it also runs into problems because of the rights employees have through the Working Environment Act.

“The Norwegian Working Environment Act focuses on dialogue and cooperation. The Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions and the other trade unions are still very much focused on this, while interest among employers has dwindled. Too often they see that they can get away with hard HRM form a legal point of view. They simply point to the fact that employees should be loyalty to the leadership.”

In some instances, like when there is a danger to the environment and safety, Norwegian employees not only have the right to sound the alarm. If there is danger to human life, they also have a duty to do so.

“It is difficult to give general advice for how employees should act. But one advice could be to not call yourself a whistleblower. Because that lands you in a legal situation where you are simply entitled to compensation if you are punished – and not protection against being persecuted by your employer.

“It is a much better idea to simply quote the constitution and the freedom of expression which everybody in Norway has,” says Dag Yngve Dahle.

- Modern muzzle

-

Dag Yngve Dahle (above) has written the book Moderne munnkurv (Modern muzzle) together with Maria Amelie. It looks at Norwegian employees’ freedom of expression, and list a range of examples of workers being reprimanded by employers for talking about their workplace. The author is pictured next to the Oslo City Hall, where some of the construction workers from the 1930s became models for Per Palle Storm’s sculptures. Are employees equally valued today?

- Maria Amelie

-

is the book’s co-author. She is also the author of Ulovlig norsk (Illegally Norwegian) and Takk (Thank You), which created a lot of debate about Norwegian asylum policies in 2011. During the past five years she has been working as a journalist focusing on the labour market, technology and entrepreneurship. In 2015 she was named Norway’s best startup journalist.

Dag Yngve Dahle has previously written Orden og oppførsel. Karakterer på jobben? (Order and behaviour. Grades at work?) (2014). He is a sociologist and journalist and works on a PhD on collective decision making in the workplace.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook