Iceland facing watershed moment as PM calls snap elections

Iceland is heading for snap elections in November after the right-left coalition of Bjarni Benediktsson collapsed in October over a range of disagreements. Political scientists were not surprised and some predict a watershed moment in Icelandic politics.

Icelandic politics is in turmoil. There were signs of increased difficulties in the coalition of the Independence Party, the Progressive Party and the Left Greens before the then Prime Minister, Katrin Jakobsdóttir, leader of the Left Greens, quit politics and ran unsuccessfully for president.

Polls had already shown falling support for the coalition parties, and some even showed the Left Greens would get zero MPs in an election. Still, the cooperation between Jakobsdóttir and Independence Party leader Bjarni Benediktsson seemed to be going well.

A contentious issue

But things soon started to sour when Jakobsdóttir left and Benediktsson took over as Prime Minister.

But things soon started to sour when Jakobsdóttir left and Benediktsson took over as Prime Minister.

In September, the deportation of a Palestinian child suffering from a rare disease was stopped by Minister of Justice Gudrun Hafsteinsdóttir, an Independence Party member.

This came after a request from the Minister of Social Affairs Gudmundur Ingi Gudbrandsson, who was then interim leader of the Left Greens.

After that, the boy was granted asylum. Immigration is one of the most contentious issues between the two parties. Rumours circulated that the Left Greens had threatened to terminate the government if the boy was deported, but that has not been confirmed.

The end of the coalition

Then, at the Left Green annual conference in early October, Svandis Svavarsdóttir was elected new leader. The conference produced a statement saying that the coalition had reached the end, and it would be for the best to have elections next spring.

The government’s term was supposed to end no later than September 2025. There was a proposal at the conference to put out a statement saying that the coalition should be terminated but that did not go through.

Bjarni Benediktsson said a few days later that if the Left Greens would not change their minds, the best thing to do would be to have elections as soon as possible. And that is what happened.

He called a press conference on 13 October to announce that he had decided to terminate the coalition and ask the President to dissolve parliament and call elections for 30 November. After discussions with other political party leaders, that is what she did.

Unconventional government

Ólafur Þ. Harðarson, professor emeritus in political science at the University of Iceland, says that the formation of the government in 2017 had been unconventional since the parties furthest to the right and furthest to the left came together in a coalition.

Ólafur Þ. Harðarson is a professor of political science at the University of Iceland. Photo: Hallgrímur Indriðason

“Many were not optimistic that this coalition would last long. Previous coalitions had lost a lot of support between elections, and therefore their majority. And mid-term polls indicated that the same would happen to this government, even though the cooperation was going well.”

But then came the pandemic, and in three months the coalition went from polling at just over 30 per cent to over 60 per cent. That lasted more or less until the 2021 elections.

“The government survived because the voters believed that it had done a good job in the fight against Covid,” Harðarson said.

Falling approval ratings

This government became the first since 2003 to maintain its majority between elections. But soon in their second term, when Covid was no longer an issue, ideological differences between the Independence Party and the Left Greens started to create more difficulties.

And at the same time, the government’s approval ratings fell drastically.

A thoughtful Katrin Jakobsdóttir a year before she decided to resign and instead run in the presidential election, which she did not win. Photo: Björn Lindahl.

“Katrin Jakobsdóttir was considered to be the one who kept the government together, and she took her role as Prime Minister to hold it together very seriously. She was the one who bridged the differences between the parties. She was for a long time the most popular politician in the country and was by far the most popular candidate for Prime Minister after the elections.”

More disputes post-Jakobsdóttir

Harðarson says that as soon as Jakobsdóttir left the government, the dispute between the Independence Party and the Left Greens got tougher, which led to Benediktsson announcing the termination of the government. The Left Greens then refused to continue in the coalition until the elections and left it instantly.

“The Left Greens risk vanishing from parliament and believe that their best bet now is to distance themselves from the Independence party and reconnect with their roots. Their loss is caused by people who don’t like that the Left Greens entered the coalition, and this certainly contributed to Jakobsdóttir losing the presidential elections.”

Loss of mutual trust

Harðarson also says that there was mutual trust between Jakobsdóttir, Independence Party leader Bjarni Benediktsson and Progressive Party leader Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson. Benediktsson, however, did not seem to work equally hard to keep the coalition together when he became Prime Minister.

“Many Independence Party members have wanted the coalition to end, and the main reason is polls that indicate the party could be in for its worst results in its history.”

Harðarson does not think immigration and energy will be the main topics for the upcoming election, despite having been hot topics recently. He believes the main focus will be the legacy of this government.

“The government parties have been criticised for how they have handled the economy and public service. Many areas of public service have been inadequate, and both inflation and interest rates are currently high. I believe the campaign will focus on that."

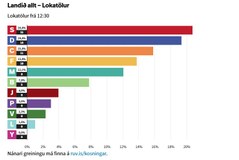

Polls indicate watershed elections

The latest polls indicate that the Social Democrats will become the biggest party after the elections while the Independence Party will reach an all-time low. Harðarson says that if the results are anything like that, it would be a watershed moment in Icelandic politics. He does expect the polls to change before election day.

“It would be historic if the Independence Party no longer is the largest party. That has only happened once before, in 2009 after the financial crisis. And it’s increasingly likely that the party will end up in opposition, which it has been for only a period of four years since 1991.

“That kind of position for a political party is rare in Western politics. It can be compared only to the position the Social Democrats held in Scandinavia in the 20th century – and they are not as dominant now as they were before.”

- Bjarni Benediktsson

-

met President Halla Tómasdóttir on 15 October to submit his government’s resignation. The president accepted the resignation and asked the current government to serve in a caretaker role until a new government could be formed after the parliamentary election set for 30 November. Bjarni Benediktsson is also the leader of Iceland's Independence Party.

- Update 2: New Government promises EU referendum

-

A Government consisting of the Social Democratic Alliance, the Liberal Reform Party and the People‘s Party was formed 21 Dec. The new government is headed by Kristrún Frostadóttir, the chairman of the Social Democratic Alliance.

Minister of Social Affairs, Labour and Housing is Inga Sæland, chairman of the People‘s Party.

The new government has agreed on a new political platform. A national referendum on continuing negotiations on Iceland’s membership of the European Union will be held no later than 2027.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook