“Paternal leave extremely important to reach gender equality"

“Today’s paternal leave legislation gives employers a lot of room to negotiate with men whether they should take leave or not. We need less flexible solutions,” says Anne Lise Ellingsæter, who has led a Nordic inquiry into parental leave. It proposed to reserve 20 weeks’ leave for the father.

Anne Lise Ellingsæter was the first keynote speaker at the Nordic Work Life Conference 2018, held at the OsloMet university from 13th to 15th June. The inquiry led by her came up with what is so far the most radical proposal when it comes to the length of paternal leave in the Nordic region:

“The time has come to take the next step towards equal parenting. The inquiry proposes a dual parental leave model. For health reasons, leave should be earmarked the mother for three weeks before and six weeks after birth. Beyond this, the period should be divided into two equal parts. The remaining 40 weeks should be shared equally, so that mother and father get 20 weeks each,” the commission proposed.

The inquiry was concluded on 6th June this year. In the end, the Norwegian parliament decided to keep today’s three-way leave; 15 weeks are reserved for each parent, 16 weeks can be distributed freely.

Paternal leave has proven to be a pretty accurate measure for how far gender equality in the workplace has come. When authorities shorten the period of leave reserved for the father, men quickly reduce their leave. This happened in Norway in 2014, when the government reduced the number of weeks reserved for the father from 14 to 10.

“When you have weeks that can be used by both mother and father, the mother usually ends up taking all of it. Old norms and habits still guide how parents think, but workplace conditions do too,” says Anne Lise Ellingsæter.

“In Norway we still hear stories of employers who believe fathers should not use more than their quota. You hear arguments like men having jobs which they cannot be absent from, at least not for prolonged periods of time. Nobody asks the same questions about the mothers.

“That is why flexibility creates a problem for men. They must argue with their employers for why they should stay at home with the child for parts of the flexible period. This creates imbalance.”

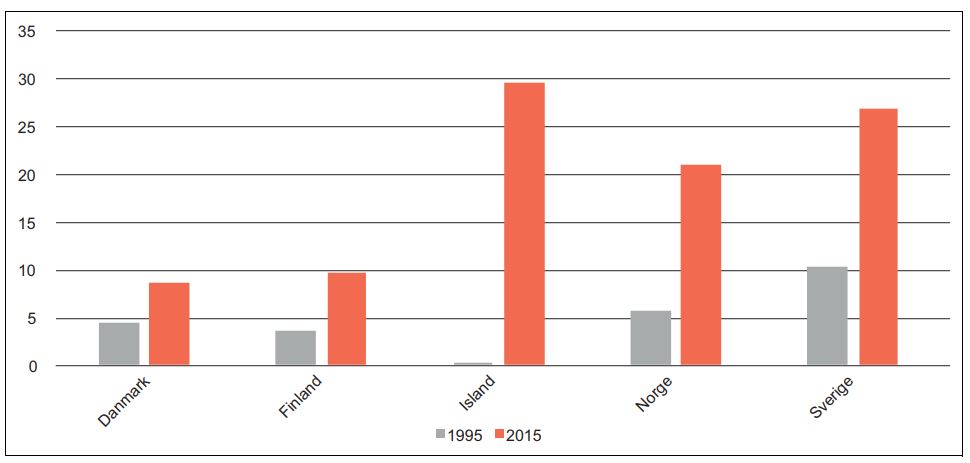

There are big differences in paternal leave between the Nordic countries. The number of weeks reserved for fathers vary from zero in Denmark to 15 in Norway. The graph below shows how the real use of paternal leave has changed over the past 20 years.

The graph shows how men have been using parental leave in the Nordic countries. The grey column is 1995 while the orange is 2015. The left axis is the number of weeks. Source: NOU 2017:6

Iceland is not only the country where fathers take the most parental leave – the increase has come from nearly nothing.

“In 2012 Iceland decided to extend parental leave to 12 months. The new system kept the period divided into three, but rather than keeping three months each for mother and father and three months to share equally, it will now be five months each and two months which are flexible,” says Anne Lise Ellingsæter.

Because of the finance crisis that hit the country, the reform has yet to be implemented however.

One difference between Norway and Sweden is that the parental leave period stretches out for much longer in Sweden.

“There, parents are expected to save parts of the leave nearly until the child is ready for school. In Norway we are very clear that the child should have one parent at home full time during its first year.”

In Sweden, parental leave has been changed to prevent immigrant women having prolonged periods of parental leave if they have several children in quick succession, which can prevent them from entering the labour market.

“What is interesting is that once you introduce a system, it becomes the norm for what citizens feel is the correct way of looking after children. Nearly all Norwegian children now attend kindergarten. If you ask mothers, a large majority also believe this is the best solution for the child.”

Anne Lise Ellingsæter is convinced that the rest of Europe will follow the Nordic region and increase parental leave – but perhaps not for the same reasons as Nordic countries, where the idea of gender equality has been prominent. Ironically, Denmark might be forced to reintroduce a period reserved for the father because of a new EU directive.

“There is a gender equality ideology behind our proposal for less flexibility. The aim is to make men and women equal, not only as workers but also as carers. But how do you achieve that?

“The paternal quota has been extremely important, symbolically, in order to change the way we think about the relationship between fathers and children. There is potential here to take this one step further by giving fathers a more equal distribution of parental leave,” concludes Anne Lise Ellingsæter.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook