The Oslo model brings transparency to the construction sector

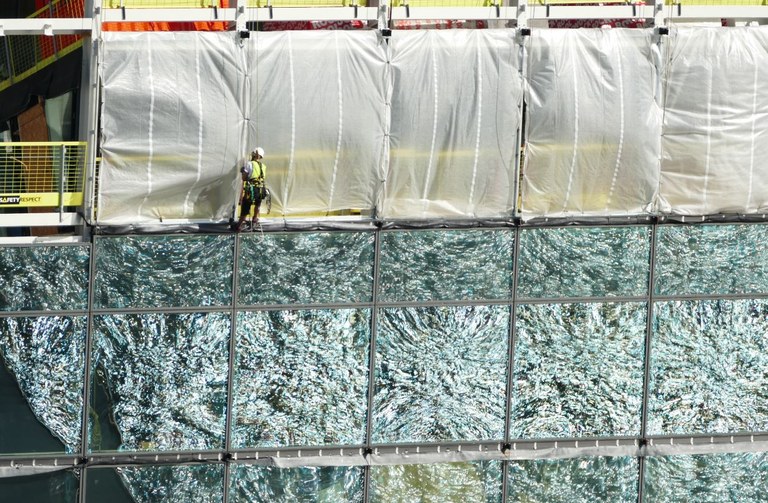

The view is dizzying as one of the construction workers climb the steps at the top of the new Munch Museum which is being built in Oslo. The museum will be more than a shop window for Norwegian culture; the construction project is also meant to be a showcase for fair competition and working conditions in the construction industry.

When the Oslo model was presented just over a year ago, the chosen location was in front of the new Munch museum. The model consists of new standard contracts and rules aimed at preventing tax evasion and the exploitation of workers. Construction companies must also use more apprentices.

“The City of Oslo will lead the fight against labour market crime and for a decent working life,” said Oslo’s Governing Mayor Raymond Johansen during the presentation.

The City of Oslo is, after the Norwegian state, the country’s largest procurer issuing contracts worth 26 billion kroner (EUR 2.67bn) every year. Much of that sum is for the construction of new buildings and facilities.

“We will now introduce even stricter demands for companies delivering services to the City. We use our purchasing power and launch standard contracts with demands which we hope will become a national standard for a serious labour market,” said Raymond Johansen.

The offensive came partly as a result of former Aftenposten journalist Einar Haakaas’ book in which he mapped criminal networks from Albania which had ended up running much of the local painting and decorating trade.

“They have worked for the Ministry of Defence, The Norwegian Tax Administration, the Government offices and a range of other public buildings,” he wrote in his book “Svartmaling” (“Painting it black”),

“Other things were disclosed too; vulnerable workers have been seriously exploited with no proper terms of employment. This challenges our Norwegian model, and is about to change our society in quite a dramatic way,” said Raymond Johansen.

There are many foreign construction workers at the new Munch Museum too, including Sylwester Petrow from Poland. He is not hired in, however, but on a permanent contract with one of the main contractors.

Most of the contracts for the Munch Museum were entered into before the launch of the Oslo model. But the model has been long in the making, explains Jonas Bals, an advisor at the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions, LO.

“It started with the Skien model, which was followed by a range of different models in places like Oslo, Trondheim and Sarpsborg. What is important is the double effect of keeping cowboy companies out and to halt the trend of certain occupations within the construction industry slowly disappearing altogether,” he says.

Conditions vary for different parts of the country, which could justify a certain variation of regulations – like how many apprenticeships should be offered. But the ambition is to make the Oslo model national, and to introduce similar regulations to the cleaning and transport sectors.

“Oslo is the one place in Norway where introducing change is the hardest. There were so few people in the capital applying for a painters’ education that not a single class was established, despite the fact that Oslo is growing at record speed. Carpenters and bricklayers are under threat too.”

The large number of hired labourers meant that just 19 percent of Oslo bricklayers were Norwegian in 2014. There are a lot of foreign labourers working on the construction of the new Munch Museum too. As we take the lift up to the 12th floor, signs are written in Norwegian, English and Polish.

The views are formidable, but the Munch Museum will be hosting fragile art. Edvard Munch had several outdoor ateliers where some of the paintings were left outside all winter – in certain cases for four years. This accelerated the ageing process. Temperature and light must therefore be regulated to stay within certain limits which are narrow even for a museum.

“The humidity should be at 50 percent with no more variation than five percentage points, and temperature must be a steady 22°C, with a variation of one degree up or down regardless of how many people are present in the exhibition halls at any given time,” explains Marit Enerhaug from Oslo Kulturbygg, who is showing us around.

All this calls for specialists among the workers, just as the architecture by Spanish architecture firm Estudio Herreros does.

“One of the most difficult tasks has been installing the large glass windows on the part of the façade that tilts forwards,” says Marit Enerhaug. The overhanging façade means the water from the basin in front of the museum is mirrored in the glass, and it looks like the workers are climbing around in moving water.

Before the Oslo model was introduced, the construction workers’ union managed to get acceptance for designating certain buildings as “Lighthouse projects”.

"The Oslo model's demands must be part of all relevant contracts entered into since May 2017. By the end of the first six months of 2018, 230 contracts are covered. Certain big projects, like the new Munch Museum and the new central library, where contracts were signed before the Oslo model was introduced, the companies have been asked retrospectively to follow the regulations as far as possible," says Robert Steen, Vice Mayor for Finance.

For Veidekke, one of the contractors that won the contract to provide both the foundation and the framework for the building, the Oslo model is more about the fact that all construction companies are now forced to do what the most serious among them have already introduced.

“We have 230 apprentices at Veidekke, and many years ago we already introduced the rule that there should be no more than two layers of subcontractors,” says head of information Helge Dieset.

In 2016, 27 percent of the City's construction contracts included demands to use apprentices, according to Vice Mayor for Finance Robert Steen.

"So far this year, this number has risen to 36 percent," he says.

To make it even clearer where responsibilities lie, the City also demands there should be no more than one subcontractor.

“We fully support the drive to secure fairer working environments and competition within the construction industry. Most of the new regulations represent no problem. But we are often forced to seek dispensation for the rule of only two layers,” says Erik Økland, who has had the most experience with the new regulations – and he is speaking about ordinary school buildings.

“The fact is that for certain things, like ventilation systems, we can order one system from one supplier. But they do not have any staff to install it, and have given a few builders’ companies licence to do it.

“We must be able to document that the subcontractors are serious. This leads to some extra work, but it goes quicker after a while,” says Erik Økland.

At the Munch Museum there are very strict environmental demands. The building is constructed to be a passive house, and it must use less energy than the old Munch Museum – despite being five times bigger. This leads to even more subcontractors.

“But the main point is not whether there are one or two layers. What’s important is that you no longer have the completely chaotic subcontractor layers which existed before,” saysJonas Bals.

Norwegian authorities have prioritised the fight against work-related crime for several years now. Six different agencies now work side by side in a new system of cooperation. The Norwegian government has also launched an initiative to create a similar collaboration in a pilot project together with an EU country.

One of the measures introduced to Norwegian construction sites is that all must be registered.This is being followed up with a separate tool, called HMSREG.

"Since this was introduced, we have seen a very positive development in the number of employees who are registered. Earlier, up to 40 percent of people working on a construction site might be unregistered. This has now fallen to three percent," says Robert Steen.

He points out that the so-called HMS cards which employees must visibly carry are important both for security and to fight work-related crime.

“I believe we turned a corner in the fight against work-related crime when construction managers themselves experienced being called in to police interrogations. This was no longer something that was happening way down the subcontractor layers,” says Jonas Bals.

- Three cultural landmarks under construction

-

Oslo is experiencing a building boom. Parallell with the construction of the new Munch Museum, two other cultural landmarks are scheduled to finish next year: A new central library and a new National Art Museum. The three buildings will have a combined area of 100 000 square metres in total.

- The Oslo model in short

-

- Those working on commission from the City of Oslo should mainly be on permanent contracts.

- At least 50 percent of those carrying out the work should be certified.

- There should be at least ten percent apprentices in areas where this is needed.

- All workers must be registered from day one.

- A right to insight into all issues that are relevant to the contract.

- Only one layer of subcontractors.

- No cash payments. All transactions must be electronic.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook