Workplaces must take the ageing workforce into account

When the workforce ages, workplaces face new challenges. This is particularly true for occupations where physical work makes up nearly all of the working day, according to Maria Albin, the keynote speaker at a European high-level conference on the working environment to be held in Bilbao in November.

Maria Albin is Professor of Occupational and Environmental Medicine at Karolinska Institutet, and spent two years on the Commission for Equal Health, established by the Swedish government in 2015. Its task was to propose measures for how to bridge the health gap in Swedish society. On 21 November, Albin is the keynote speaker at the Health Workplaces for all Ages, organised by the European Agency for Safety and Health at work, EU-OSHA.

Maria Albin is Professor of Occupational and Environmental Medicine at Karolinska Institutet, and spent two years on the Commission for Equal Health, established by the Swedish government in 2015. Its task was to propose measures for how to bridge the health gap in Swedish society. On 21 November, Albin is the keynote speaker at the Health Workplaces for all Ages, organised by the European Agency for Safety and Health at work, EU-OSHA.

“In Sweden we work into old age, in Norway they work even longer and the Icelanders are world leaders. This development is necessary, because we live longer and must finance the pensions,” says Maria Albin.

“Yet at the same time we see the problems arising out of this development. Especially within physically challenging jobs. The mental capacity is rarely a problem when people get older, but after 40 their physical strength quickly fades.”

Muscle mass halved

A 90 year old only has half the muscle mass of a 20 year old. When you turn 50, your muscle mass is reduced by one to two percent a year due to natural processes. This development could accelerate due to factors like a bad diet, a lack of physical exercise and chronic inflammation.

“In many occupations you use your physical strength nearly to the limit, like in the care sector and construction industry. When you have to work until you are 60 to 65, and preferably until 70, in order to maintain a decent pension, it becomes too exhausting,” says Maria Albin.

She sees the need for a ‘mid-life conversation’, where people talk with their employer about how to adapt their working situation. If not you risk an elder generation which no longer manages to fulfil the demands of the job, resulting in lower retirement pay and bigger social gaps.

“We need a planned career path, because these are predictable problems. We need better matching between the individual’s abilities and work demands. If not people will be asked to do things they cannot do. In certain occupations, like cleaning, this both means making the job easier to perform, and looking after the skills which the individual possesses. Older people might be good in other areas, they can be mentors or work with planning.”

A need for skills improvement

Society as whole needs to contribute too, says Maria Albin:

“We need a safety and training package where you can improve your skills in mid-life.”

If employers fail to see the importance of looking after the older workforce, legislation might also be necessary.

The Netherlands has introduced rules limiting the number of hours older people can work with waste collection. For the rest of the time, they have to drive the waste truck or do other tasks. But this does not solve the problem of the gap between people increasing with age. That is why it is better to make it easier to introduce individually adapted solutions in workplaces.

“For older people it is not only important to reduce the amount of physical work. You also need to give them more hours to recover.”

There is, however, risk connected with introducing individual rules for older workers. If this is not done in cooperation with the social partners, such rules can further increase age discrimination.

“The way workplaces adapt to the ageing workforce will be different in different countries, and between different workplaces. But systematic measures are needed to stop differences increasing even more.”

A large health gap

The Nordic countries enjoy high levels of income and are considered to be very egalitarian, yet there are still major differences when it comes to health. One way of looking at this is to note the life expectancy in different groups of people. Since this continues to rise, the ‘normal’ age to die is also changing. In Sweden the normal age to die is 89 to 90 years for women, and between 85 and 90 for men, regardless of education levels.

If you compare groups with different levels of education, those with a higher education live longer on average than those with only upper secondary education. There is also a gender difference – women live longer than men in all education groups.

After reaching 30, women with only secondary education live on average another 51.4 years. Women with further education live on average five years longer, another 56.4 years. For men the difference in further life expectancy is even larger between people with lower and higher educations – a full 6.4 years.

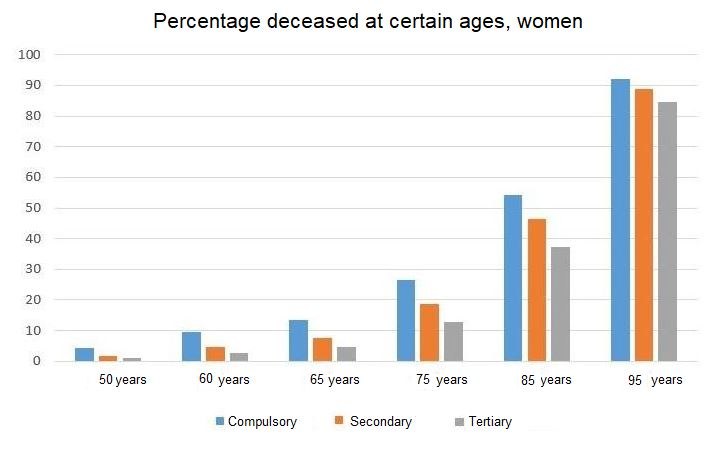

Another way of looking at this is to see how many have died at a certain age. In the bar chart above the number of women who have died are divided into three different education groups. The taller the bar the higher the mortality.

“There is a debate around whether these differences stem solely from the fact that people with higher educations get jobs that are less staining and risky, or whether the education itself has an impact on life expectancies,” says Maria Albin.

“The idea is that people with a higher education are better equipped to handle a complex workday, and that this has a positive effect on their health.”

But do any studies show this? Do highly educated immigrants who only get low-skilled work live longer than immigrants with a low education who drive a taxi?

“It is impossible to say, since not being able to work according to your education also has negative effects,” answers Maria Albin.

When the commission for equal health finally presented its recommendations, they were not so much focused on how the health care sector should be reorganised or improved. If you want to eradicate the differences in health, you need to broadly and systematically improve things from the beginning of people’s lives – with well-developed maternal health care, improved education and – as a result – better chances of finding a job.

“There simply are no shortcuts when you want to reduce the health gap. To bridge that gap you need to take many steps going in the same direction, through a process where you create ownership for the parties concerned,” the commission concludes.

One of the suggestion the commission made was to establish a new, national centre for knowledge about and the assessment of working environments.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook