Who will look after Sweden’s growing elderly population as birth rates fall?

Between 2013 and 2023, the number of people in Sweden aged 25 to 60 rose by 455,000. By 2033, that number is expected to grow by a further 13,000 people. There is a similar development in the rest of the Nordics and the EU, which for many municipalities means severe labour shortages.

For years, the impending labour shortage has been rumbling in the background. There has, of course, been talk about the coming need for assistant nurses, doctors and nurses, as well as labour shortages in many other professions – not least in the green investment schemes in the north.

There has also been talk about declining birth rates and an ageing population. But suddenly, the issue seems to have exploded, even as dramatic international news is fighting for people’s attention.

On the same day, the Dagens Nyheter newspaper reported that 16 preschools in Norrköping were closing because there were simply not enough children.

“This demographic development is one of the greatest challenges I have faced as a municipal politician,” Maria Sayele Behnam, a Social Democrat and chair of the education committee, told DN.

Later that day the same paper published a story titled “The skills shortage in elderly care – a major challenge.”

“We have long been talking about the ageing population, so that’s not news. Birth rates have also fallen sharply in recent years and we are now really seeing the effects,” says Bodil Umegård, head of section for the employer policy department at the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, SKR.

Slowing growth in the number of working people

One of her tasks is to analyse demographic changes from municipal and regional workforce supply perspectives. The figures fluctuate depending on who is considered to be part of the workforce.

If everyone between 20 and 66 is included, projections show an increase of 166,000 people by 2033. However, according to SKR’s latest economic report, the main population growth will occur in the age groups 20 to 24 and 61 to 66 – when young people are usually in education and the over-60s are working less.

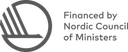

The increase in the working-age population is unevenly distributed between municipalities. In one municipality, for example, the working-age population is expected to grow by nearly 14 per cent by 2033, while in another municipality, it is projected to decrease by 11 per cent.

Illustration: SKR

In reality, employment is the main activity for people aged between 25 and 60. In this group, the workforce is set to grow by just 13,000 over the next decade, according to SKR’s latest projections.

“The change that will occur between 2023 and 2033 is significant. There are various reasons, but one of the main ones is the changes to migration policies. Between 2013 and 2023, foreign-born citizens represented the entire growth of the working-age population while also contributing to an increase in birth rates.

“Now the increase of foreign-born people in the workforce has slowed down considerably as a result of a drop in the number of asylum seekers and work permit applications,” says Bodil Umegård.

Big increase in foreign-born municipal employees

In the ten years before 2023, foreign-born citizens played a major role in increasing the labour force, not least in the elderly care and health sectors. Between 2013 and 2023, the proportion of foreign-born municipal employees rose from 13 to 22 per cent and from 14 to 19 per cent in the regions.

“Foreign-born citizens have been an important group in the labour market, not least in the elderly care sector in big cities. Today, 35 per cent of assistant nurses, nearly 50 per cent of care assistants and 40 per cent of doctors in Sweden were born abroad,” says Bodil Umegård.

Many municipalities are preparing for the coming labour shortages. Some already struggle to fill vacancies, especially in elderly care. And with an ageing population, the need keeps growing.

Bodil Umegård, head of section, the employer policy department at the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, SKR. Photo: Hans Alm

The baby boomers born in the 1940s are getting old and need more care. In the current ten-year period between 2023 and 2033, the number of people over 85 will increase by 60 per cent.

Many stay healthy for longer and their needs will be postponed, but sooner or later, municipal elderly care will have to step in to help most people.

“It is positive that we live longer and can enjoy more healthy years, but when the large groups born in the 1940s need care, it will be noticed not only in elderly care but in the healthcare sector in general,” says Bodil Umegård.

There is a significant need to recruit workers for the elderly care sector across the country but this is particularly pronounced in smaller municipalities that already struggle with an ageing population, less tax revenue, high retirement figures and young people moving out.

The working-age population will shrink in six out of ten municipalities by 2023. Northern municipalities are seeing the biggest drop, but municipalities further south, including Blekinge, Gävleborg, Dalarna and Värmland, also see a fall in their working-age population.

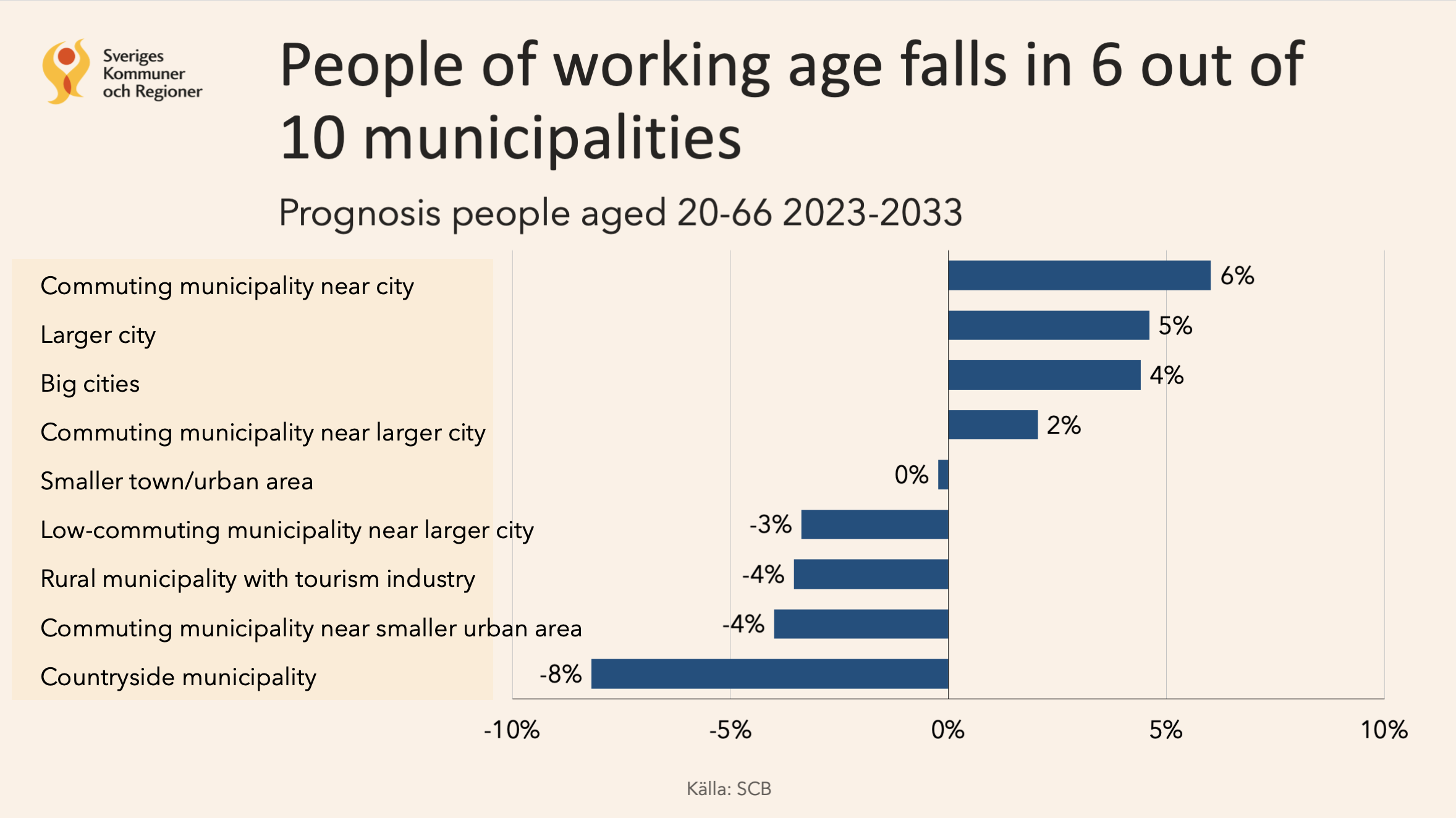

Unless major changes are made, 75,000 more employees will be needed in municipalities to support elderly care, disability services, and upper secondary education during this period.

While the need for staff in preschools and primary schools is expected to fall by 47,000, many industries will still be competing for available workers. In parallel with the labour shortages, Sweden also has high unemployment figures.

What are the chances of finding workers among the unemployed?

“Yes, Sweden has one of Europe’s highest unemployment rates. But the potential here is not as big as you might think. Many of the unemployed are full-time students. There is a certain potential among the others, the majority have weak connections to the labour market and do not have the skills for welfare sector jobs.

“Long-term measures are needed to make them employable, based on the employers’ skills supply needs,” says Bodil Umegård.

Working on a solution

So what to do? Many Swedish municipalities are working on this, not least to secure labour in the health and social care sectors. The solution is not to hire more staff, those people will not be available. Instead, the municipalities are looking for ways of reducing the need for more staff.

It will be crucial to be able to make use of and develop existing employees and find new ways of working. One way would be to turn part-time positions into full-time ones. Today, one-third of staff in the elderly care sector work part-time, on average 29 hours a week.

“There’s a big potential here. A lot would be achieved by improving work environments and making it possible for part-time employees to work an extra three hours a week. We could also motivate more people to postpone their retirement,” says Bodil Umegård.

If nothing changes, demographics – with the significant increase in the elderly population – will lead to a 32 percent increase in the need for employees by 2033 compared to the number of employees in 2023. Illustration: SKR

One part of the strategy is to protect those who already work in the elderly care sector and offer them training and new ways of working, while also strengthening the managers' ability to lead.

Many who work in elderly care have high sick leave rates and another strategy is to work with factors that promote health and prevent sick leave. There is also scope for improvement by investing in new technology and new ways of organising elderly care.

What role would increased wages play in getting more people to apply for jobs in the elderly care sector?

“Salaries are important for what professions and employers people choose, but there are other important factors like skills development and career opportunities. Municipalities need to show that they offer both meaningful jobs and collective agreements with good conditions and benefits.

“Making this visible to existing and potential employees is a strategy that can secure the supply of skills. In elderly care, there are secure jobs and meaningful work. This is highly valued by young people.

“In this sector, you can make a difference, which is something many young people seek,” says Bodil Umegård.

- Swedish municipalities

-

There are 290 municipalities in Sweden. Stockholm is the largest with 955,574 citizens (2024). Dorotea is the smallest with 2,294 citizens (2024).

- Common challenge

-

There will be fewer people available to take care of the elderly. Photo: Mads Schmidt Rasmussen, norden.org

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook