Fresh report: Nordic citizens can work anywhere in the region. So why don’t they?

It would seem we are so comfortable in our home countries that we see few reasons to apply for work in or move to a different Nordic country.

Nordregio researchers have been asked to investigate how the common Nordic labour market has developed over the past 70 years. They have also asked some questions to try to find out what the future might bring.

This has resulted in the report The Common Nordic Labour Market 70 Years and Beyond, presented to the anniversary conference 70 Years of a Common Nordic Labour Market.

Not so integrated after all?

Nordregio researcher Anna Lungren says the report confirms something the researchers already knew something about from previous surveys – that moving and commuting between the Nordic countries is really not that common.

“We used to think that there was more migration than there actually is,” Anna Lundgren tells the Nordic Labour Market. She is one of several Nordregio researchers who have been working on the report.

In light of the Nordic governments’ vision for the Nordic region to become the world’s most integrated and sustainable region, these numbers is slightly bad news, believes Lundgren.

Some of the numbers show that:

- Fewer than half a million people out of a total population of 27.5 million were born in a different country from where they currently live.

- 1.6 per cent live in a different Nordic country than the one they were born in.

- 0.5 per cent of the Nordic population commute to a different Nordic country. The European average is 1 per cent.

Three main trends

The Nordregio researchers highlight three main trends when looking back on 70 years of a common Nordic labour market.

Inhabitants from islands and autonomous territories – like Greenland, Åland and the Faroe Islands – move more often to a different Nordic country than other Nordic citizens.

Proximity is important, both geographical, linguistic and cultural. This is relevant both for migration and commuter patterns – getting a job in a different Nordic country is simply more common if distances are not too large.

One of the central attributes of Nordic migration patterns is re-migration, meaning many Nordic migrants spend a little time in a different Nordic country, for instance finding work while unemployment is high in their home country, getting new work experiences, for family reasons, to study and then move back home again after a few years.

The border commuters

Getting a job in a different Nordic country does not necessarily mean moving to that country. For obvious reasons, this is more common in cross-border areas like the Øresund region (Denmark and Sweden), Innlandet-Värmland (Norway and Sweden) and Tornio-Haparanda (Finland and Sweden).

In some municipalities more than 10 per cent of the workforce commute from a neighbouring country, according to the report.

In later decades, and especially during and after the pandemic, remote and hybrid work has become more important in the Nordic region.

Development patterns in the Nordic countries:

Sweden

Historically migration from Finland to Sweden has been the largest. Immigration from Finland reached a top in 1969 and 1970 with around 40,000 people annually. Re-immigration to Finland has been the second-largest migration stream since 1954.

Besides migration from Finland, immigration from Denmark in 1975 stands out. This was probably due to increased unemployment in Denmark following the oil crisis. Danish immigration to Sweden also rose in the mid-2000s after the Øresund Bridge opened.

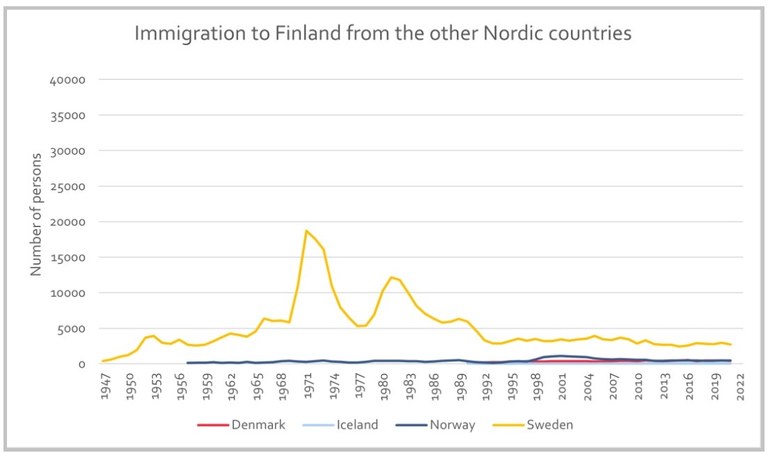

Finland

Emigration from Finland to Sweden was quite high even before the 1954 agreement on a common Nordic labour market.

Developments in Finland are in many ways related to what has already been mentioned about Sweden.

Emigration from Finland mirrors immigration since a majority of those who went to Sweden returned to Finland.

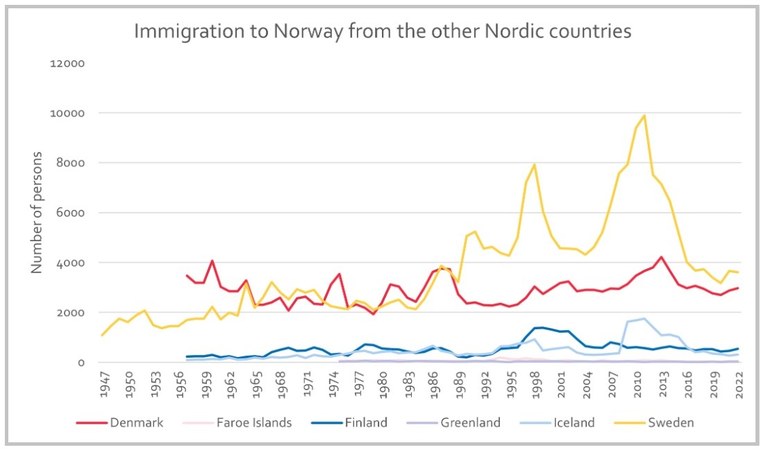

Norway

Migration has been fairly stable through the years with certain exceptions, which mainly relate to migration to and from Sweden.

The top came in 1989 when more than 11,000 people migrated to Sweden. The reason was a downturn in the Norwegian economy. Many of the Norwegians soon moved back to Norway.

Swedish immigration and emigration top the statistics, while Danes make up the second largest group.

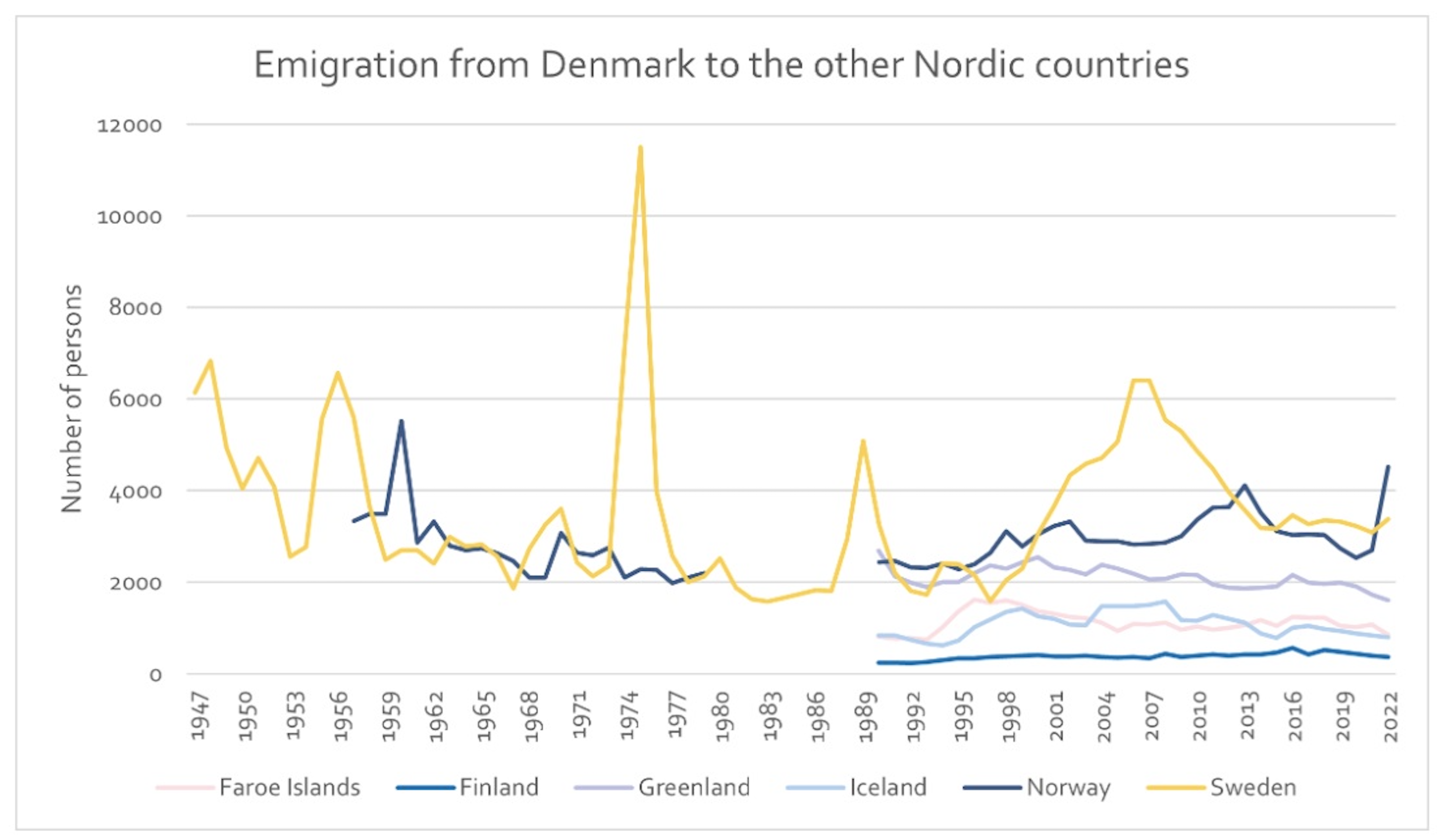

Denmark

The largest migration stream from Denmark came in 1975, when nearly 12,000 people emigrated to Sweden. This was driven by an economic downturn during the oil crisis.

Norwegians make up the largest group of migrants to and from Denmark.

What is unique for Denmark is the high level of immigration from Greenland and, to a lesser extent, the Faroe Islands.

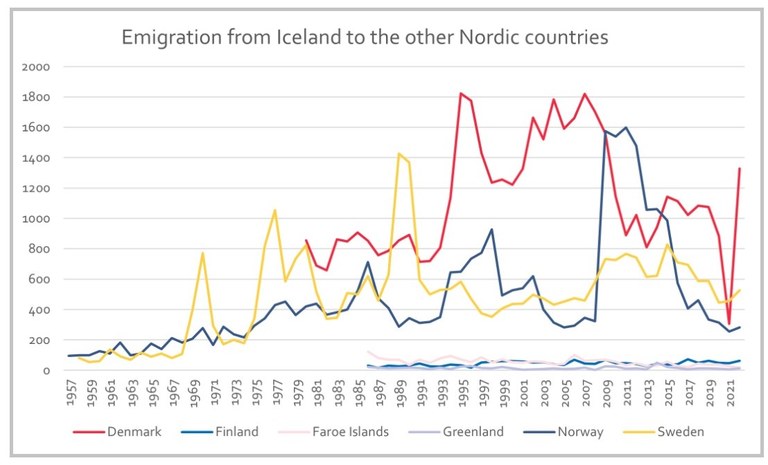

Iceland

Iceland’s migration pattern is less stable, with migration to Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Migration to Sweden happened in waves in the 60s, 70s and 80s, and reached a top in 1989.

The largest number of immigrants to Iceland come from Denmark. Denmark has also been a popular destination for emigrating Icelanders.

During the financial crisis, many moved from Iceland to Norway.

Moving when we have to

Migration between the Nordic countries has receded since the 2000s. Some of the reasons given by the researchers include:

- All the Nordic countries’ economies are fairly doing well. There are fewer economic incentives than earlier to move to a different Nordic country.

- The world has become smaller. Increased globalisation means we can move (nearly) wherever we want, at least within Europe.

- It is not necessarily uncomplicated to move to a different Nordic country to work and live there. Known obstacles include tax rules, regulations and access to social welfare, electronic ID and recognition of educations.

The migration can be explained in different ways. It could be economic downturns and high unemployment at home, job prospects, higher wages, better working conditions, lower living costs and a better quality of life in a neighbouring Nordic country.

- But the prospects of a better life is about more than work. The advantages to moving must surpass the disadvantages, the researchers point out. Even if it pays financially to move, we might still choose not to. The social transactions also help decide whether we move or not.

If there is a desire to increase labour market mobility in the Nordic region, the researchers believe it is important to dismantle said barriers.

“If you do not absolutely have to move or commute to another Nordic country, but perhaps fancy trying, your motivation does not increase if you end up struggling with a lot of red tape to make it happen, says Lundgren.

Language is a barrier

The report also includes a survey of people who are interested in the Nordic labour market. Some labour market experts in the Nordic countries have also been interviewed.

The results confirm that bureaucratic and administrative barriers are considered to represent the greatest barrier to a more integrated Nordic labour market.

- 56 per cent site bureaucratic and administrative barriers like taxation, problems related to electronic ID cards and different regulations for social welfare.

- 54 per cent say languages are a challenge.

- 51 per cent mentioned difficulties coordinating family life.

- 43 per cent said it is difficult to find housing.

The researchers were surprised to find that more than half of the respondents listed languages as a barrier to working in a different Nordic country.

Nordregio researcher Anne Lundgren wonders whether the reason might be that the older generation had a greater interest in and understanding of the Nordic languages than today’s generation. Nowadays, much communication happens in English.

Lundgren believes it is important to understand each other’s languages because this influences many other things.

“When we don’t understand each other’s languages, we understand less of our countries’ similarities and differences.”

Competing for the same workforce

All the Nordic countries face similar challenges like ageing populations, low fertility figures and an industrial society dependent on technology. The same Nordic countries also have a great need for labour in many of the same sectors – health, engineering and in business.

The report says the entire Nordic region faces a lack of hundreds of thousands of vocationally trained workers within 10 to 15 years from now.

Similarities between the Nordic countries can make it easier to get a job in a different Nordic country, but the researchers believe it is more likely that the Nordic countries have to compete for the same labour force.

In the future, we need to get better at using all of the available workforce, and labour immigration from other countries is an important part of this, concludes Nordregio researcher Debora Pricila Birgier.

“No matter how well the Nordic countries manage to utilise their common labour force, it will not be enough,” the researcher says.

- Taking stock after 70 years

-

Anna Lundgren is a Nordregio researcher. She is one of the researchers behind the report on the state of the common Nordic labour market.

- New report from Nordregio

-

The Common Nordic Labour Market 70 Years and Beyond.

By Anna Lundgren, Debora Pricila Birgier, Nora Sánchez Gassen andGustaf Norlén

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook