More culture, less bureaucracy – the keys to a more mobile Nordic labour market

By 2030, the Nordics should be the world’s most integrated, sustainable and competitive region. The open Nordic labour market is key to fulfilling that ambition. But mobility is low and may need to be stimulated by administrative and cultural measures, according to recent research.

Nordic citizens have enjoyed a common labour market for almost 70 years. This has included the freedom to move across Nordic borders and to find employment in any of the Nordic countries.

Yet despite this opportunity, fewer than 1.7 per cent of workers choose to move to work in a different Nordic country. Only 0.5 per cent live in one country and work in another.

Migration patterns have been fairly alike in most of the Nordic countries and territories since the early 1990s, according to Anna Lundgren and Ágúst Bogason at the international research centre Nordregio in Stockholm. They published two reports in June – “Competence Mobility – How can labour market mobility in the Nordic Region be increased” and “Re-start competence mobility in the Nordic Region”.

Anna Lundgren and Ágúst Bogason from the Nordregion research centre.

“It is reasonable to consider that free mobility is key to fulfilling the vision 2020, especially in the border regions. That is where you find the big potential. A bigger labour market brings the possibility of better matching, which again creates more jobs and higher growth.

“Today, though, mobility between the countries is not that impressive, and actually lower than the EU average. Yet on an international scale, mobility within the Nordics is pretty high,” says senior researcher Anna Lundgren.

Regional voices on mobility

As part of the project, Ágúst Bogason has looked into the driving forces behind Nordic labour mobility – and obstacles to it – across three regions: Greater Copenhagen, Vestfold Telemark and Greenland.

He interviewed around 40 representatives from the business sector, municipalities, regions and trade unions. He also interviewed people who have chosen to apply for work in a different country or just across the border. What tempts people to seek work in a different Nordic country, what makes it easier and what are the obstacles to cross-border work?

“It is not necessarily straightforward to accept a job on the other side of the border. You need a personal number from the other country, a digital ID, a bank account and you need to understand the tax and pension systems,” explains Ágúst Bogason.

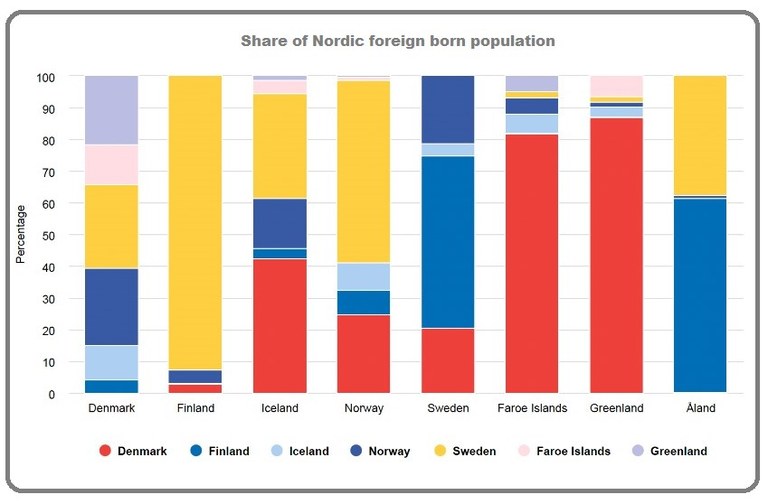

The researchers at Nordregio have made an illustration of the origins of the population born in another Nordic country. Denmark has the most differentiated Nordic population, on Åland the Nordic immigrants almost entirely comes from Finland and Sweden. Source: Nordregio.

The fact that the cross-border labour market is less than seamless became clear during the pandemic. When Swedish workers suddenly no longer could travel to their jobs in Norway, it soon became clear that the safety nets were not strong enough. Who would pay compensation for those who could no longer turn up at work, for instance? And how would the employment insurance schemes work in this unusual situation?

“It is true that we are not talking a huge number here, but for the individuals concerned the uncertainty meant a lot,” agree Anna Lundgren and Ágúst Bogason.

Driving forces, attractions and obstacles to mobility

Higher pay is one common reason for looking for work in a different country, as are beneficial exchange rates. Swedish doctors and nurses have for a long time been tempted to take long or short-term jobs in Norway. Today, the Norwegian krone is weaker and interest has waned.

“The Covid-19 pandemic and consequent limits to free movement put a damper on cross-border mobility. Over time, it might also have an impact on the trust needed to get a job in a different Nordic country,” according to both researchers.

The Copenhagen region has also tempted job-seeking Swedes in the Öresund region with its lower unemployment rates and higher wages. The latest statistics from 2021 show that 16,914 people commuted across Öresund daily. 95 per cent of them lived in Sweden and commuted to Denmark.

Recent figures show an increase of 17 per cent during the first six months of 2022 of Swedes commuting to Denmark to work. Higher wages and more available jobs are issues that impact the Nordic labour market, but there are other factors at play too.

“Social and cultural aspects are also attracting factors. People might be on the search for an adventure, to try something new, or it could be the beautiful Norwegian scenery for instance,” says Anna Lundgren.

Norwegian nature tempts Swedes to the country, including those who want to work in a different country. Photo: Björn Lindahl

But social and cultural differences can represent an obstacle too, especially when it comes to language skills. Older generations often have better knowledge of and understand different Nordic languages than the younger ones. There is also a range of bureaucratic difficulties that throw spanners in the work both for people moving to a different Nordic country and for those who remain in their home country while working across the border.

“It ought to be easy to do the correct thing. Today there is a lot of frustration in the regions that it takes so long to remove red tape and that national legislation does not take into account the regions’ needs to a sufficient degree,” says Anna Lundgren.

Proposed improvements

Anna Lundgren and Ágúst Bogason point to three issues that they believe are important when it comes to improving labour mobility. The first is to improve the coordination of laws and regulations between the Nordic countries to make it easier to work across borders.

A digital ID system that would work in all of the Nordic countries, allowing for access to banks and public services, is crucial, they argue. They also highlight the need to simplify tax systems and the right to social security for border commuters.

The second is to support initiatives aimed at boosting interest in Nordic cultures and languages, in order to improve integration. In recent years, partly because of globalisation, interest in Nordic issues has fallen. That is why targeted measures aimed at boosting knowledge about language and culture – not least among younger people – will be particularly important. To improve mobility rates, more information about the opportunities to study and work in a different Nordic county is also needed.

The third is to improve Nordic cooperation on all levels in order to stimulate free movement between the Nordic countries.

“It is important to synchronise the systems better so that those who want to work across borders or in a different Nordic country don’t lose their social rights,” says Ágúst Bogason.

- Sweden on the horizon

-

If you get high enough in Copenhagen, like in the tower next to the Danish parliament, you can see Sweden on the other side of the Öresund Bridge. Yet despite the short distance, not many people choose to move there.

Fewer than two per cent of Nordic citizens live in a different country from their native one – a figure that is considerably lower than the EU average.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook