The male role in the Nordics – in crisis or developing?

Two authors from Denmark and Sweden have written books on the male role – one concluding it is in crisis, the other believes it is evolving. Yet both underline the importance of jobs and highlight the negative consequences faced by men who cannot find one – especially among immigrants.

“Is there a male crisis at all, and if so, how does it manifest itself?” asks Swedish psychiatrist and author Stefan Krakowski in his third book, Incel – about involuntary celibacy and a male role in crisis.

When the Nordic Labour Journal repeats the question, he answers:

“It depends how you look at it. I believe we have a crisis in as much as men’s role in recent decades has changed in different ways in line with socio-economic conditions. This has been a rapid development. Women’s elevation to economic independence has led to a radical change to the man’s traditional role as the family provider and being the one who takes the initiative to courtship and relationships.”

The Nordic Labour Journal puts the same question to Danish sociologist and author Aydin Soei. He answers:

“If you look at the vast majority of men, there is no crisis. There is rather a change for the better as we move away from stereotypical portrayals of men who cannot show emotions, who leave the carer role to women and who maintain the old male role as the family provider.”

As these answers demonstrate, this question is complex and depends on a range of individual and social factors. What follows is some aspects of the male role in the Nordic region of today.

Work means status

A crucial factor here is the Nordic labour market, which has changed radically in step with increased digitalisation and automation. Repetitive manual jobs – traditionally held by men with low levels of education – hardly exist anymore.

“The need for low-education labour is very limited in Sweden – perhaps the lowest in the whole of Europe. This means many people fall outside of the labour market. A man without a job is not an attractive man,” says Stefan Krakowski.

“This is not the case only in the labour market. Someone’s employment status is important in close relationships too. Despite the fact that Sweden is one of the world’s most gender-equal countries, women chose men according to certain patterns – meaning their education level and earning potential.”

We might be witnessing a shift, says Stefan Krakowski, alluding to surveys that show younger women more often chose men with low education levels.

The two books about the male role talk about two different groups – men with no relationship to women and men who have become fathers.

Drawing conclusions from male research performed by Men’s Health Society, a network in which many Danish municipalities participate, Aydin Soei says that men tie their identity to professional accomplishments and to the fact that the man’s position in the labour market is the largest challenge when it comes to status and recognition.

“If you are male and fail to find work, you lose respect and status. When jobs do not demand an education, educated men are marginalised and might lose out also when it comes to love, sex and their relationship to the opposite sex,” he says.

And while the number of low-skilled jobs has fallen dramatically, Nordic women’s liberation and increased independence carry on, as demonstrated in the Nordic Labour Journal’s latest gender equality barometer. The division of power has never been more equal in the Nordics.

Parenthood offers something new

Parenthood can create an alternative identity that represents both a relief and a gift, believes Aydin Soei.

“Many men use parenthood as leverage in order to become more wholesome people. It allows them to be more affectionate, and to show feelings that are associated with mothers,” he says and explains that new Danish fathers spend twice as much time with their babies today compared to ten years ago.

“The fact that more fathers want to take an active part in their children’s lives is a revolution, a success and the greatest change to norms in the welfare state,” says Aydin Soei.

This is a gift not only for the men but also for the children and women, he says. The more time spent caring for the child, the more time is freed up for the women.

“In the long run, this will narrow the gap between men and women and improve the work-life balance.”

Aydin Soei also highlights another survey which shows that the higher the education level, the more time fathers spend talking to their children and following them to football training and other activities. And vice versa. The lower the education level, the less time is spent with the children.

“Those who spend the most time with their children, also spend the most time with their work. So this is a question of priorities and parental culture,” says Aydin Soei.

What is more, points out Aydin Soei, parenthood cannot be taken away – unlike jobs and careers.

Childless men lose out

Men who do not become fathers are the focus of Stefan Krakowski’s book. Those who do not find a partner and therefore live in involuntary celibacy (incel = involuntary celibate).

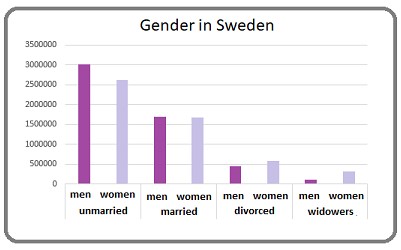

Sweden’s male surplus and the growing group of men who neither manage to establish a family nor find a job is a ticking bomb, he argues.

Gender distributions in Sweden according to Statistics Sweden, divided into four groups. Registered partners are counted as married, and divorced if the relationship has ended. There are nearly half a million more unmarried men than women.

“This situation leads to frustration, anger, political extremism and even assaults on women. We are only seeing the tip of the iceberg, and that is why we need to talk about this,” says Stefan Krakowski.

Ethnic differences – and the differences between generations

But let’s go back to parenthood, the focus of Aydin Soei’s fifth book about ethnic minorities in Denmark and the other Nordic countries. The book is called Fædre –fortællinger om at blive til som far (Fathers – stories about becoming someone as a father). In it, he has interviewed five Danish men, all of them with immigrant backgrounds.

“In Denmark, men with immigrant backgrounds are the most stigmatised parent group, but immigrants do not make up a homogenous group,” says Aydin Soei.

He sees great differences between first and second-generation immigrants when it comes to how they view children and childcare.

“Some of the immigrants have fled countries with authoritarian child-raising ideas which are common in countries with poor social safety nets. They end up in the Nordic region, which has the most permissive and softest upbringing in the world, where we see children as individuals with their own rights. This is an enormous cultural chasm for the first generation of fathers from non-Western countries,” he says.

The authoritarian ideas do not trickle down to the second generation immigrants, however – those born and raised in Denmark and who also make up a group that is twice as large as that of their fathers, explains to Aydin Soei.

“They wish to care for their children, to be supportive and to be a role model. These are things they often missed from their own fathers because they were probably absent or had ended up with a considerably lower status in their new home country,” he says.

School results with consequences

Both Krakowski and Soei underline the importance of education to fight mens' alienation in the labour market and in family situations.

“A young man with poor grades starts out at the bottom, and this leads to an unfortunate domino effect. Failing in school leads to failure in the rest of your life,” says Stefan Krakowski.

He puts his hope in new curricula and courses for Swedish elementary schools which are coming in this autumn. These should take into account the different starting points that girls and boys have at that age.

“Boys’ brains mature slower than girls, and unfortunately there is also an anti-learning culture among boys,” says Stefan Krakowski

Aydin Soei points to the link between poor school results and opinions around gender equality. He encourages everyone to be concerned about the losers in Nordic elementary schools.

“They are prone to subscribe to old-fashioned gender roles based on the idea that a man is worth more than a woman. That is the last thing you can cling to when you have failed in your role as a family provider and has nothing else to tie your identity to. How we get them to succeed in elementary school is crucial – regardless of whether they are called Peter and Hans or Hassan and Ali,” he says.

- Danish and Swedish views of the male role

-

Aydin Soei from Denmark (above left) and Stefan Krakowski from Sweden have created debates about the male role in their respective countries.

- Aydin Soei is a sociologist who has done research on and written several books about ethnic minorities, risky behaviour and vulnerable children and areas. He was behind the Tingbjergundersøgelsen, a survey of 14-15 year-olds in a school and their relationships to and thoughts about hashish, violence, education and the future.

- Stefan Krakowski is an author, writer, chronicler, podcaster and senior psychiatric consultant. He has worked for SOS International on security issues, as an analyst at the Swedish Armed Forces Headquarters and as a Swedish representative at the Human Right Committee at the European Council in Strasbourg.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook