The Öresund Bridge is 20, and gets a sub-sea equivalent

The bridge linking two Nordic countries is 20 years old this summer. The link has been important for the Öresund region’s development. It is also important for the massive project of securing a permanent link between Zealand and Germany.

The Öresund Bridge was inaugurated on 1 July 2000. It was a time of cross-border optimism, increased mobility and borderless economic and technological development, says Professor of Strategic Communication Jesper Falkheimer in the new anthology Checkpoint 2020 – People, borders and vision in the time of the Öresund Bridge, published by the Centre for Öresund Region Studies together with Øresundsinstituttet.

The Öresund Bridge was inaugurated on 1 July 2000. It was a time of cross-border optimism, increased mobility and borderless economic and technological development, says Professor of Strategic Communication Jesper Falkheimer in the new anthology Checkpoint 2020 – People, borders and vision in the time of the Öresund Bridge, published by the Centre for Öresund Region Studies together with Øresundsinstituttet.

Falkheimer describes the Øresund Bridge as “both a physical entity and a symbol for the transnational regionalisation in Europe”.

A region reflecting its surroundings

Commuting by ferry, hovercraft or catamaran had long been the norm for many cross-border commuters. Yet the Öresund Region only became a well-known term among many Danes and Swedes when the bridge arrived in the Nordics’ southernmost border area. Then, as now, the region mirrors its surroundings, Jesper Falkheimer tells the Nordic Labour Journal.

“The Öresund Region is a microcosmos for what is happening in society as a whole. Take the introduction of border controls on both the Danish and Swedish sides. This shows how global events impact those of us who move around in the region.

“But since the region is a political construction and has no real regional independence, it falls flat when something like this happens – like the introduction of border controls – and things then often end up in Stockholm or Copenhagen.”

Falkheimer has documented media coverage of the Öresund Region and considers the birth of the region to be a communication issue in many ways.

“Media coverage has been and continues to be crucial, but the hype around the inauguration of the Bridge 20 years ago has faded.”

Which does not mean the Danish-Swedish coverage will disappear, he thinks.

“It will ebb and flow like it has been doing for another 100 years. Right now we are at a low ebb with national currents. Journalism remains very national – the Öresund Bridge has not managed to change that. But who knows what will happen in the future,” says Falkheimer.

There were great expectations to the Öresund Bridge when it was being constructed 20 years ago. Photo: The Öresund Bridge.

A bridge that pays for itself

The link consists of more than the bridge itself. There are onshore constructions on both sides – the artificial island of Pepparholmen and a tunnel on the Danish side because of traffic to and from Copenhagen Airport, Scandinavia’s largest airport – and convenient direct train connections to Stockholm, Gothenburg, Karlskrona and Kalmar.

The whole thing was financed through loans on open financial markets, with Denmark and Sweden as guarantors. This infrastructure project model is common in Denmark but not in Sweden.

“Our income is from road traffic and railway fees, which allows us to pay back any loans taken out. Along with developing the region, this is our core task,” Caroline Ullman-Hammer, the Öresund Bridge Consortium CEO, tells the Nordic Labour Journal.

Caroline Ullman-Hammer has been CEO for the Öresund Bridge Consortium for 14 years. Photo: Louise Houmøller/The Öresund Bridge.

As she steps down from that position after 14 years this autumn, some 600,000 customers have a BroPass tollroad contract. An average of 20,400 vehicles crossed the Bridge every day in 2019 – around 5,500 were single journeys with a BroPass commuter agreement. Nearly two thirds of the 30 billion Danish kroner construction costs (2000 money) have already been recouped.

A great lift for the cities

Numerous surveys have shown that customers are very happy, and paying for the Bridge has gone according to plan – bar for a major fall in traffic due to Danish Coronavirus restrictions. Caroline Ullman-Hammer is also happy that it is possible to see the effects the Öresund Bridge is having on a physical level.

“The Bridge is a success story both for rail and road, and it still has a lot of space and capacity. It is also a shining example of how Copenhagen and Malmö have been brought together, as seen in comprehensive city developments near the Bridge on both sides over the past 15 years.”

The roof of the Emporia shopping centre in Hyllie, where many Danes travel to shop. Photo: Björn Lindahl

Ullman-Hammar mentions the two new neighbourhoods that have grown in the wake of the Öresund Bridge – Ørestad and Hyllie - both constructed nearer the Öresund link than to Copenhagen's and Malmö’s city centres. They have their own train stations and a lot of new housing and offices for businesses of all sizes – and many new jobs. Many visitors from near and far have been interested in seeing the innovative architecture and clever climate solutions applied to the new neighbourhoods.

Most important of all, in a labour market perspective, is the fact that many companies – new and old – have chosen to set up headquarters or branches near the Öresund link.

New traffic solutions

Public transport has also increased considerably after the Öresund Bridge was constructed. On the Danish side, Copenhagen Metro is being expanded beyond the underground system’s current four lines. On the Swedish side, the Citytunnel has constructed two new train stations in Malmö and turned the central station from a terminus into a station where trains can pass through.

This year, decisions will also be made on two further Öresund links: A tunnel between Helsingör and Helsingborg called the HH link, and an expansion of the Copenhagen Metro to Malmö.

The next step

The Fehmarn Belt Link is part of the EU’s plans to link the Nordic capitals as well as Scandinavia to the Mediterranean with a rail network called the ScanMed Corridor. This is part of the Central European TEN-T transport network.

Construction work on the Danish side should have started already, but the Corona pandemic postponed this until 1 January 2021. The Leipzig federal constitutional court in Germany is due to make a decision in October.

“We do not expect the German court to reject the application, only perhaps to make some adjustments in response to some local concerns,” says Thomas Becker, the Managing Director of String – Southbaltic Transport Regions Implementing New Geography.

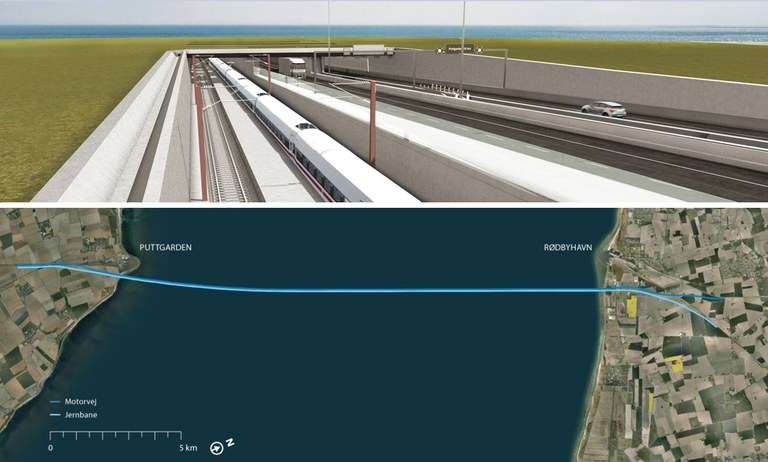

A sub-sea tunnel is to be constructed between Puttgarden in Germany and Rødbyhavn in Denmark. This would allow for uninterrupted travel a straight line from Oslo to Germany without using a ferry. Illustration: femern.com

String is a political organisation with members in Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Germany, working to promote a sustainable infrastructure in and between the countries, while creating a common green industry hub.

“The level of industrialisation is far greater in Northern Europe than in the rest of Europe. We also have a much higher GDP, a higher educated workforce, a politically peaceful situation and comprehensive polytechnic knowledge. According to the OECD, we are also leaders in green industry, energy, water, waste, sun and wind power,” says Thomas Becker.

Regional drive with potential

Thomas Becker welcomes a green transport link with electrified trains, but also wants to highlight the benefits of the 18 kilometres long sub-sea tunnel between Denmark and Germany.

Thomas Becker is Managing Director of String – Southbaltic Transport Regions Implementing New Geography – a political organisation with members in Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Germany. Photo: Johan Wessman/News Øresund.

“The Fehmarn Belt Link is Northern Europe’s largest infrastructure project ever, and a great chance to turn Northern Germany, Denmark, Norway and Sweden into a mega-region for green industry with plenty of new jobs,” he says.

For this to happen, the countries involved need to agree on a joint strategy and gather under one common brand, he thinks.

“Right now the plans are far too fragmented, but if we really coordinate and market ourselves as a leading green hub we can become an attractive muscle for growth, just like Silicon Valley has been for the tech industry,” says Thomas Becker.

He sees the Fehmarn Belt Link as an integration project and an opportunity to compete internationally within B2B.

“Green industries offer green solutions to other industries. Here we can compete with China when it comes to finding solutions that will make their production of for instance electric bikes more efficient. In Northern Europe we are world leaders in this,” says Thomas Becker.

The Fehmarn Belt Link is positive for the Öresund Region

Both Jesper Falkheimer and Caroline Ullman-Hammer are very positive to the Fehmarn Belt Link. The professor of strategic communication says:

“I believe the link will be enormously important to economic development, also in the Öresund Region. I am less sure whether the views, community and identity among our region’s citizens will change, but in terms of the economy and sustainability it is absolutely right to build the Fehmarn Belt Link.”

And the Bridge CEO puts it like this:

“We have made certain long-term calculations, but believe developments linked to the Fehmarn Belt Link will outmatch these, as the Öresund Region will get a completely different lift when Hamburg comes so close. This will spill over into both Denmark and Sweden.

“In Sweden I believe it will become possible to set up several clusters if the state handles it well. Around Stockholm, on the west coast and in Skåne, and allow such a development to create synergies and new perspectives.”

She is particularly keen to create new perspectives based on her Swedish background. She lives in Sweden and works with both Swedish and Danish colleagues in Denmark.

“For me it has been beneficial to see issues from a broader perspective when it comes to security, personnel, market and media issues, as both Danes and Swedes are quite dissimilar here. Our mindset has also been never to speak English to each other. Everyone should understand Danish and Swedish, and you do that even if you cannot speak the language. If you want to understand, you do.”

- More than concrete – a regional brand

-

News Oresund and Rapidus are the two media whose main focus is on what is happening across the sound.

Regional brand and the region

The debate about how to secure more international attention as well as a stronger regional brand for the Öresund Region started in Denmark. This led to the creation of the Öresund Committee, a political organisation which was merged with Greater Copenhagen in 2015. In the beginning, the name was Greater Copenhagen and Skåne Committee, but after Swedish Halland joined the organisation the second half of the name was dropped.

Today, Greater Copenhagen is “a political and business partnership between Region Skåne and Region Halland in Sweden, Region Zealand and The Capital Region of Denmark and the associated municipalities. Together we work towards creating a metropolitan region built on economic growth, a growing labour market and a good quality of life for our 4.3 million citizens”.

The Öresund Region remains as a geographic area, defined by Skåne and the Danish islands of Zealand, Falster, Lolland, Mön and Bornholm. And in the middle of this region triumphs the Öresund Bridge, stretching its tall pillars skywards over Öresund.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook