What happens when the refugee stream has been stemmed?

“It’s like on a plane when the oxygen masks have been activated. When you’re told to put on your own mask before helping people sitting next to you. If we are to help the world, we must look after our own country first,” says Jøran Kallmyr, State Secretary at the Norwegian Ministry of Justice.

He has asked to meet foreign journalists in Oslo to relay his message to international media: Norway will send back nearly everyone who applies for asylum because, according to him, they do not have valid reasons to apply. This applies first and foremost to those crossing Europe’s northernmost border point, between Norway and Russia. In the past few weeks 4,500 refugees have arrived there.

The airplane analogy is problematic. Are the Nordic welfare states really under threat from the current flow of refugees? In what is beginning to look like panic, one country after the other are introducing border controls, temporary permits to stay and are generally making conditions for refugees harder.

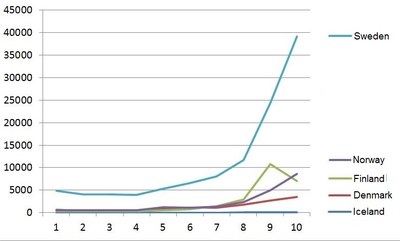

What is clear is that the increasing rate at which the number of refugees are arriving is unsustainable. You only need to take a ruler and draw the continuation of the Swedish graph in the illustration below to realise that.

Asylum applicants Jan-Oct 2015. Source: the different countries’ migration authorities

Between September and October this year the number of asylum applicants in Sweden rose from 24,307 to 39,181 people, a 38 percent increase. If that increase were to continue for another 10 months, 1.35 million asylum seekers would be arriving in Sweden. The overall for the coming 10 months would be 3.4 million asylum seekers.

But the graphs for the past ten months of asylum applicants in the Nordic countries also shows a different development — what has happened in Finland. There, the number of asylum applicants has fallen dramatically. It is very likely the other countries will also experience a fall as new obstacles to immigration are introduced.

This means the flow of refugee will probably be considerably lower in the months to come. But what will happen to those who have already crossed the border?

There is no escaping the fact that refugees cost money. Before they find work and can contribute by paying taxes which finance the welfare system, they need to learn the language, complement their educations and learn to understand Nordic societies.

Seven years to get a job

“The median time it takes for a refugee immigrant to enter the Swedish labour market is seven years,” says Joakim Ruist, who studies immigration at the University of Gothenburg.

During that time the refugees need a place to live, food, clothes and the necessary training. It is uncertain how many get permission to stay, just like it is uncertain how many of them will ask for family reunion. The refusal rate is not low, not even in Denmark, the country considered to having tightened the conditions for asylum seekers the most.

87 percent of asylum applications in Denmark were approved during the ten first months of 2015. How strict politicians can be also depends on how the flow of refugees looks like.

“Only a small part of the 4,500 who have arrived to Norway from Russia have any chance of staying,” says Jøran Kallmyr.

The tasks are also very different between countries. This is how many asylum seekers have arrived in the various Nordic countries so far this year:

| Country | Number of asylum seekers | Number of citizens per asylum seeker |

|---|---|---|

| Iceland | 291 | 1,119 |

| Denmark | 13,293 | 423 |

| Norway | 21,946 | 232 |

| Finland | 24,910 | 232 |

| Sweden | 112,264 | 85 |

| Nordic total | 172,704 | 151 |

This means 85 Swedes must share the costs and necessary work in order to look after each asylum applicant who arrived between January and October in 2015. Less than 300 asylum seekers have arrived in Iceland in the same period, meaning 1,119 Icelanders share the task of looking after one asylum seeker.

Compared to previous major flows of refugees, the current one is by far the largest since World War II. For Sweden it is also larger than what happened during the war, when 70,000 Norwegian and Danish refugees arrived, plus 70,000 Finnish children.

For Finland, the current number of refugees is dwarfed by the 400,000 people who were forced to leave Finnish Karelia after the Winter War against the Soviet Union, and who had to find places to live elsewhere in Finland.

It is difficult to measure the percentage of BNP which is being spent on newly arrived refugees instead of on the native population. Joakim Ruist has tried, and says it amounts to 1.35 percent of Sweden’s BNP. He studied a group of more than 70,000 refugees and the income and expenses they represented in 2007, and he has extrapolated this number for the number of refugees expected to arrive this year.

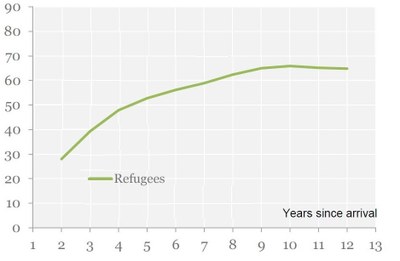

The Swedish Public Employment Office has also been looking at the employment of male refugees arriving in Sweden between 1997 and 1999. Ten years later 65 percent were employed.

Percentage of employed refugees after years of living in Sweden. Men arriving between 1997 and 1999. Time axis: Years since arrival. Source: Swedish Public Employment Office, OECD.

The sooner refugees get jobs, the sooner they can contribute to both their own costs and to the welfare system. That is why politicians prefer to talk about processing those with an education as quickly as possible.

“Politicians talk a lot about validation. For the refugees with a higher education this is of course important. But only ten percent of the refugees have that, and they make up the group with the least problems of accessing the labour market,” says Joakim Ruist.

“40 to 50 percent of the refugees who have arrived have not even finished an upper secondary education. They must first gain the necessary qualifications, then take upper secondary education and preferably get some extra training too before surviving in Sweden’s highly specialised labour market,” says Joakim Ruist.

According to him there are only two alternatives:

“You either accept more lower wages, giving more refugees a chance in the labour market, or you accept that they will receive welfare benefits for many years to come.

“The current flow of refugees will not have any immediate effect on the labour market. It has plenty of time to adapt. The immediate effect will be increased public costs,” says Joakim Ruist.

- Jøran Kallmyr

-

State Secretary in the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, meets foreign journalists in Oslo to talk about Norway’s refugee and migration policy (picture above).

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook