Hotels threatened by the sharing economy

New digital services which bring sellers and buyers together are making inroads in traditional areas of business. Most successful of them all is American Airbnb which helps people rent out their apartments. The hotel industry in Finland is fighting back.

Digital market places have made it easy to share personal services and property, like cars, machines, bikes and houses. It has quickly become a global phenomenon known as the sharing economy. What started out as idealistic projects, for instance spending the night on someone’s sofa (Coachsurfing), has become increasingly commercial.

The online service Airbnb, founded in San Francisco in 2008, has made it very easy to be a host or a guest, and as a result it has become very popular indeed. But it is also controversial. In New York, for instance, it is illegal to hire out an apartment for less than one month at a time, but already more people are staying in private houses than in hotel rooms.

In Helsinki around one thousand properties are offered on Airbnb, but it is not easy to get a Finnish host to talk about how the service operates. One person says the family rents out their apartment in the summers and during weekends when they are away or are staying in the countryside. Another host is willing to talk, but wants to be anonymous.

“The neighbours do talk, and I’m not sure how they feel about this,” a Helsinki woman tells the Nordic Labour Journal. She has just finished her studies and needs some extra cash. A friend told her about the service.

Small income

Since early last summer she and her boyfriend have been renting out their 38 square metres one bedroom apartment with a balcony some 20 times at around €60 per night. That does make for a massive income, and the apartment must be cleaned before and after the rental period. They only accept guests when they are not at home themselves and so far everything has gone well.

“But if I had more money I don’t think I would be renting the apartment.”

They have chosen to trust their guests and do not hide their valuables. Most guests are from St Petersburg in Russia. Now the couple are themselves heading to Australia for a month and have decided to put the apartment on another sharing website instead — ShareTribe, developed in Finland.

The young couple got help from a professional photographer, paid for by Airbnb, but that is the only contact they have had with the company’s Nordic HQs in Copenhagen. According to its homepage the company also covers damages up to €60,000 caused by guests.

“You find all the information you need on their homepage.”

Criticism

Timo Lappi, head of the Finnish Hospitality Association, is not happy about new service providers setting up shop without any regulations at all. One year ago his association carried out a survey which showed that Airbnb’s capacity in Helsinki was equal to that of a medium-sized hotel. One year later the capacity was four hotels.

“The company has expanded enormously and is outside of any legal regulation. We have proposed to the Ministry of Employment and the Economy that everyone should have to play by the same rules,” he says.

So far the ministry’s civil servants have been following developments, but the Hospitality Association wants new services to be regulated and it aims to push the issue forward when Finland’s next government prepares its programme after the general elections next spring. There is another problem which the association wants to address too. Hundreds of restaurants across Finland which lack an alcohol license allow customers to bring their own. This is illegal, but little is being done about it.

"The state stands to loose out on tens of millions in potential tax revenues."

The Hospitality Association has also been looking at The Restaurant Day, a popular event where everyone can sell food without any regulations, and we see that our members’ revenues fall by ten percent on that particular day. Still it is current policy not to stand up to the hobby food outlets.

Authorities content

Finnish tax authorities are keeping an eye on how the different sharing services are developing, but so far they have no plans to increase their surveillance. They do not agree with the Hospitality Association’s assessment of lost tax revenues.

“This is so small scale to be of no fiscal importance,” say tax expert Mervi Hakkarainen at the Finnish Tax Administration.

She says it is sufficient that landlords declare their rental income after adjusting for expenses.

Airbnb is not the only well-known American sharing service which has popped up in recent years. Just a few weeks ago the online taxi service Uber set up shop in Helsinki, but here the taxi trade is under stricter regulation than in Stockholm, where Uber is now very popular. So far the Uber app does not work.

In Finland there is also competing taxi services like Estonian Taxify, which cooperates with the established taxi firms. Greater Helsinki public transport also has their own app, Kutsuplus. It allows you to book a minibus at a very favourable price, which has made the service very popular.

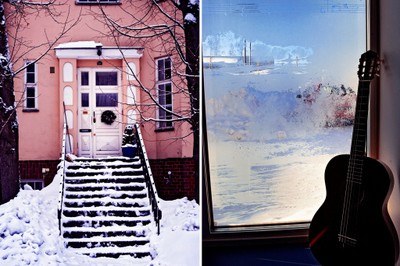

- Renting out through Airbnb

-

Since early last summer this couple have rented out their 38 square metres one bedroom apartment with a balcony, 20 times at around €60 per night.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook