Effective sanctions make Norway’s quota law a success

The law on quotas is the most efficient measure to improve the boardroom gender balance. “But the law should be followed up by effective sanctions and state measures which help stimulate the action.” That is the advice from head of research Mari Teigen to other countries looking to legislate for quotas on company boards.

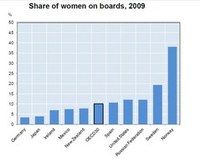

There is a lot of attention on how to improve the gender balance in Europe’s social and working life, and the debate about company boards is particularly active. Norway reigns supreme with 40 percent female board room representation in the country’s largest companies. That is twice the number for Sweden, which comes second, closely followed by France, according to a fresh OECD report. On average within the OECD area only one in ten board members in large companies is a woman.

‘Women on boards in Europe: From a Snail’s Pace to a Giant Leap?’ is the title of the EWL’s (European Women’s Lobby) Report on Progress, Gaps and Good Practice. The February 2012 report shows the progress on boardroom gender balance in nine EU countries and Norway. The report has eight evidence-based conclusions which the EWL suggests could be used to tailor future efforts on EU and domestic levels.

Some of the report’s recommendations are: it is necessary to intervene in order to increase the number of women in boardrooms, self-regulation can create a basis for legislation and quotas are most effective when followed up by sanctions. The authors use Norway’s introduction of a quota law as an example, and the fact that the aim was not reached until real sanctions were linked to the law.

Self-regulation not enough

Norway’s parliament passed the law on quotas in 2003, which says a minimum of 40 percent of either sex must be represented on the boards of a wide range of Norwegian companies. Until 2005 the companies were left to regulate this themselves, but when the number of women did not reach more than 12 percent - far off the 40 percent target - the law was implemented and it reached its full force from 2008. At the same time strict sanctions were introduced for those companies that failed to follow the law. Those that didn’t risked being dissolved.

The law covers nearly 2,000 companies, including some 350 public limited companies, publicly held companies and cooperatives. Before the law was fully implemented some public limited companies re-registered and avoided being covered by the law. This was interpreted as a protest against the process. According to the researcher this could be the case for some, but far from for all.

“The Norwegian law on boardroom quotas has been a gigantic success,” says Mari Teigen, research director at the Institute for Social Research in Oslo.

“It shows the will to act in an area which was in complete stagnation. The reality on the ground now shows us that women can have powerful corporate positions,” she says, and continues:

“The reason for this success could be that it turned out not to be so difficult to find women to fill the boardroom seats. It could also have presented some companies with the opportunity to replace some board members.

Lively international debate

Norway’s quota law had a serious impact on the debate on unreasonable gender gaps in corporate life, while the right tools were missing. When the law came into force it turned out the tools were available.

Similar legislation has since been passed in Spain (2007), Iceland (2010), France (2011), the Netherlands (2011), Belgium (2011) and in Italy (2011). Meanwhile the debate on alternative strategies to improve the gender balance has continued. After much debate, Sweden, for instance, chose an alternative strategy with no legal framework.

The increasing international debate could be linked to the fact that we now, perhaps more than ever before, recognise the power of the free market, says Mari Teigen. Who controls the big companies has become a political issue.

Domino effects

One of the ambitions of the Norwegian law on boardroom quotas was that it should create a domino effect and have an impact outside of the boardrooms too. To which extent has this happened?

“We’re in 2012 now. The law was fully implemented from 2008. This might not have been enough time to change the top management in the big companies. So we still don’t know what effect the law has had on gender equality. We don’t know enough about whether female board members have been interested in pushing for changes which are more tailored to family and working life, and we know little about whether this has had an impact on companies’ internal equality policies. What we do know is that is has not changed the gender mix in management. CEOs and other top management remain male dominated,” says Mari Teigen.

She points out that Scandinavian top management has been more male dominated than top management in British or US companies for instance. This could be linked to the fact that certain aspects of our welfare state is not conducive to gender equality, thinks Mari Teigen.

“A large public sector could be attracting many women. Career women often find better working conditions in the public sector, which makes it possible to pursue ambitions without compromising Nordic norms on the balance between work and family life. In other countries there might be clearer divisions as women either chose a career or they do not.”

Yet one important reason for male-dominated top management, she thinks, is the fact that male-dominance breeds male-dominance; men prefer men and such expectations become the prevalent culture.

A policy for businesses

There were two important issues behind the introduction of Norway’s quota law. The 1990’s saw a lively debate about the lack of female leaders, and the male dominance in economical decision-making sharply contrasted with the general developments on gender equality. Gender quotas did not represent something new in Norway either. And finally, there was deregulation of public companies. This meant gender balance regulation in public administration and committees was in danger of loosing importance. All in all these debates created a starting point for the law on boardroom quotas.

“Politicians developed a policy for businesses. There is still no gender equality policy for businesses apart form the rules on quotas, says Mari Teigen.

How have the social partners contributed to all this?

“When it comes to the social partners, the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise, NHO, has played the most interesting role. NHO has insisted on operating independently and has in principle been against the law. At the same time NHO contributed to the implementation of the law through the Female Future programme, which has helped qualify, highlight and realise female boardroom candidates,” says Mari Teigen.

She is holding a brand new edition of Social Research, Volume 29: ‘Firms, Boards and Gender Quotas – Comparative Perspectives’, which she herself has contributed to with the chapter on ‘Gender Quotas on corporate Boards: On the Diffusion of a Distinct National Policy Reform’.

- Mari Teigen

-

is a research director at the Institute for Social Research in Oslo, and head of research for the group Equality, Inclusion, Migration.

Current research themes:

Changes to legislation on discrimination, quotas on company boards, analysis of policy development on labour life and families.

- Women in boardrooms

-

Just one in ten board members in the largest companies within the OECD area is a women, according to the OECD’s new gender equality barometer.

- European Women's Lobby

-

The European Women’s Lobby (EWL) is an umbrella organisation for women’s organisations in the EU. The report is called ‘Women on Boards in Europe: From a Snail’s Pace to a Giant Leap?’ (2012).

- Female Future

-

is the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise’s drive to

- strengthen gender equality in working life

- improve female representation in management and on boards

- attract more women to the private sector

It is part of their work to secure companies access to enough skilled labour.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook