Why did Iceland do so well?

From the crisis hit in 2008 until 2011 Iceland experienced the greatest income redistribution in Europe. It is common to think that cuts are needed to deal with economic crises. Iceland is an example of the opposite. Welfare works better than cuts, claim the researchers behind the report Welfare consequences of financial crises.

Professor Stefán Ólafsson presented the results from the research, which formed part of the programme Nordic Welfare Watch in Reykjavik on 10 November. He himself was surprised by the clear picture which emerged.

“The results for Iceland are much better than expected. Securing the welfare for households works better than cuts. We see this from comparing developments in Iceland, Ireland and Greece.”

In addition to head of research Stefán Ólafsson, the research group behind the project includes Olli Kangas, Joakim Palme, Jon Erik Dølvik and Jørgen Goul-Andersen from the Nordic countries, and Mary Daly from Ireland, Pran Bennet from England, Ana M. Guillen from Spain and Manos Matsaganis from Greece. The entire project will be published as a book in the spring of 2017.

The report Welfare consequences of financial crises contains comparative studies of the policies which were carried out and the impact they had on well-being. Country-specific studies were also made. The researchers have looked at how the burdens in the wake of the crises were shared, and what approach worked best to end the crisis and maintain welfare. The Icelandic approach was to redistribute the burden by increasing taxes for higher earners and protecting vulnerable groups:

Welfare expenses were increased and redistributed towards lower and middle income groups

- The main aim was to protect the most vulnerable

- Taxes for high earners were increased, but lowered for others

- Benefits for lower earners were increased to avoid poverty

- Low and middle income earners were given debt relief

- Activation and job creation was considerably increased

- A devaluation of the Icelandic krona helped maintain higher employment levels

From the crisis hit in 2008 until 2011 Iceland experienced the greatest income redistribution in Europe.

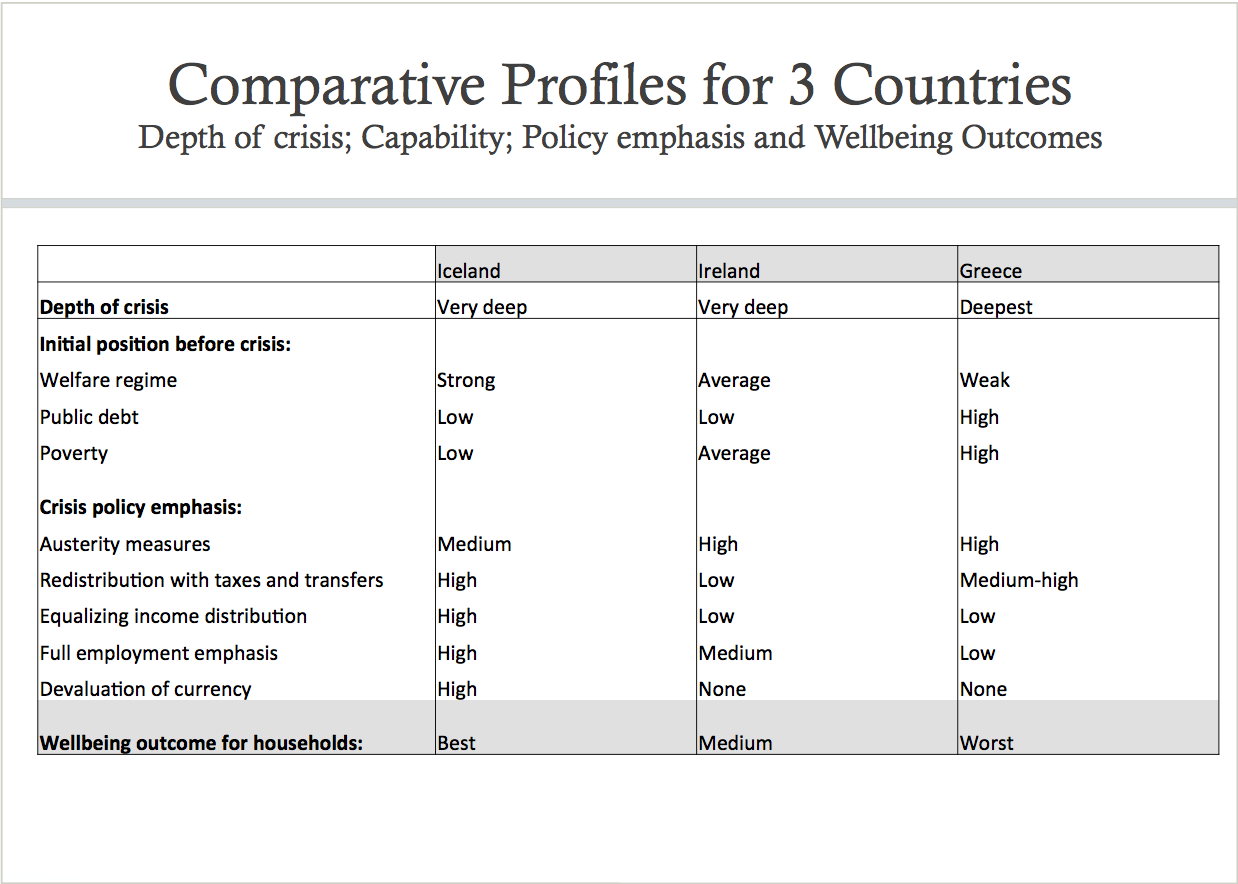

The table below is from Stefán Ólafsson’s talk and shows the comparison between three of the countries which were hardest hit by the crisis: Iceland, Ireland and Greece. It shows which policies were carried out and how this impacted on household welfare.

The comparison shows the differences between the countries in terms of how hard the crisis hit. Greece stands out as the country with the deepest crisis, Iceland and Ireland was in a deep crisis. Compared to Ireland and Greece, Iceland had a good starting point when the crisis hit.

“We were in a good situation in terms of public finances. We fell from up high, the government did not have much debt. The state debt grew a lot during the crisis, because many useful measures were initiated in order to rebalance the economy.”

In 2007, Iceland had the lowest level of unemployment in Europe. It tripled during the crisis. There was little poverty, compared to Greece where poverty was already high before the crisis.

Cuts

The table above shows the measures the governments put in place to counteract the crisis. All of the countries made cuts. But in Iceland they were moderate.

“We made some cuts, but to a much lesser degree than the other European countries which were hard hit by the crisis. Our cuts were not so serious, and did not have the major negative consequences as the ones we saw in Southern Europe,” said Stefán Ólafsson and added:

“Iceland did well in terms of using welfare resources, redistributing assets to where they were needed the most, we protected households but made cuts to health, education and administration.”

Making ends meet

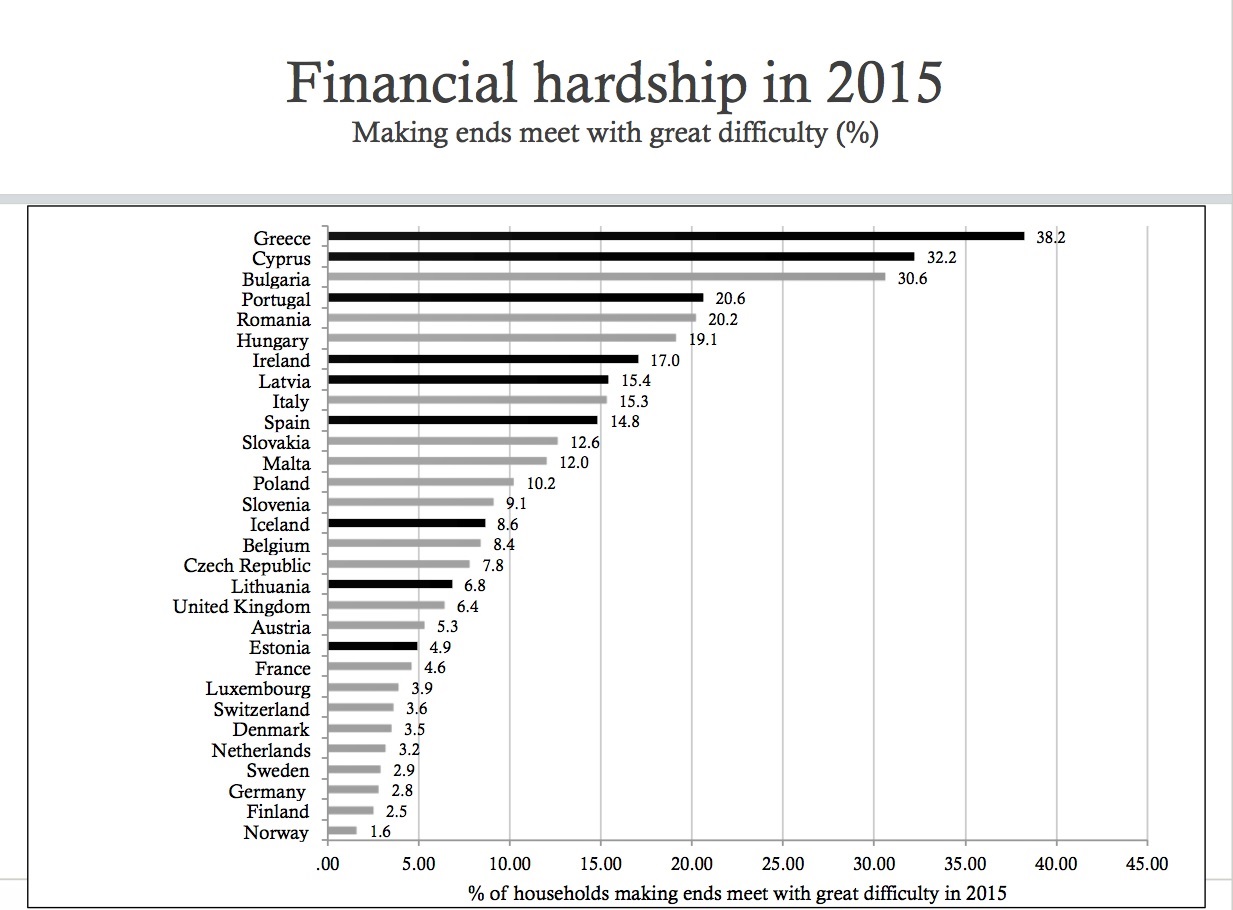

The table below shows the consequences of the crisis. It shows the size of the countries’ populations struggling to make ends meet in 2015. The countries represented by a black line were the hardest hit.

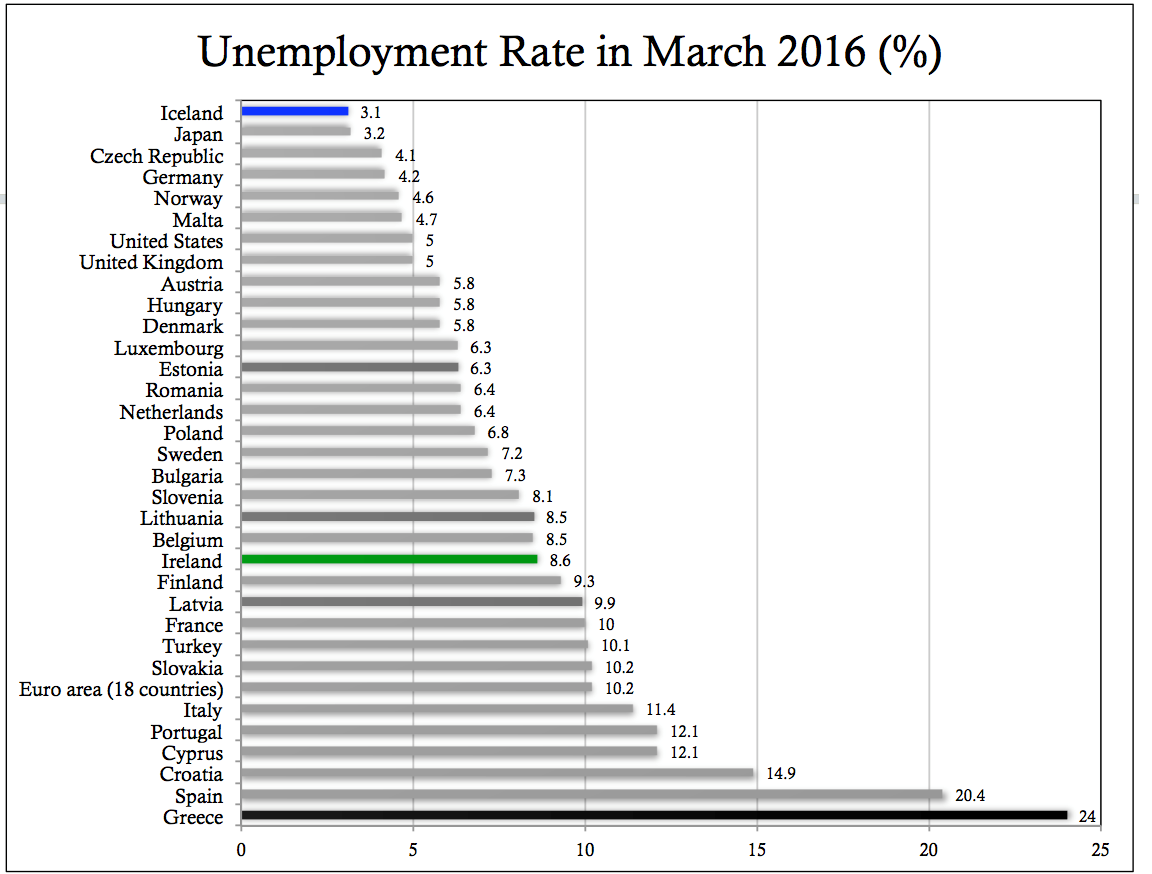

Unemployment is another measurement for how well the countries have recovered from the crisis. In March 2016, Iceland had the lowest unemployment rate in Europe at 3.1 percent. Greece had the highest, at 24 percent, and Ireland’s unemployment stood at 8.6 percent, according to Stefán Ólafsson’s table:

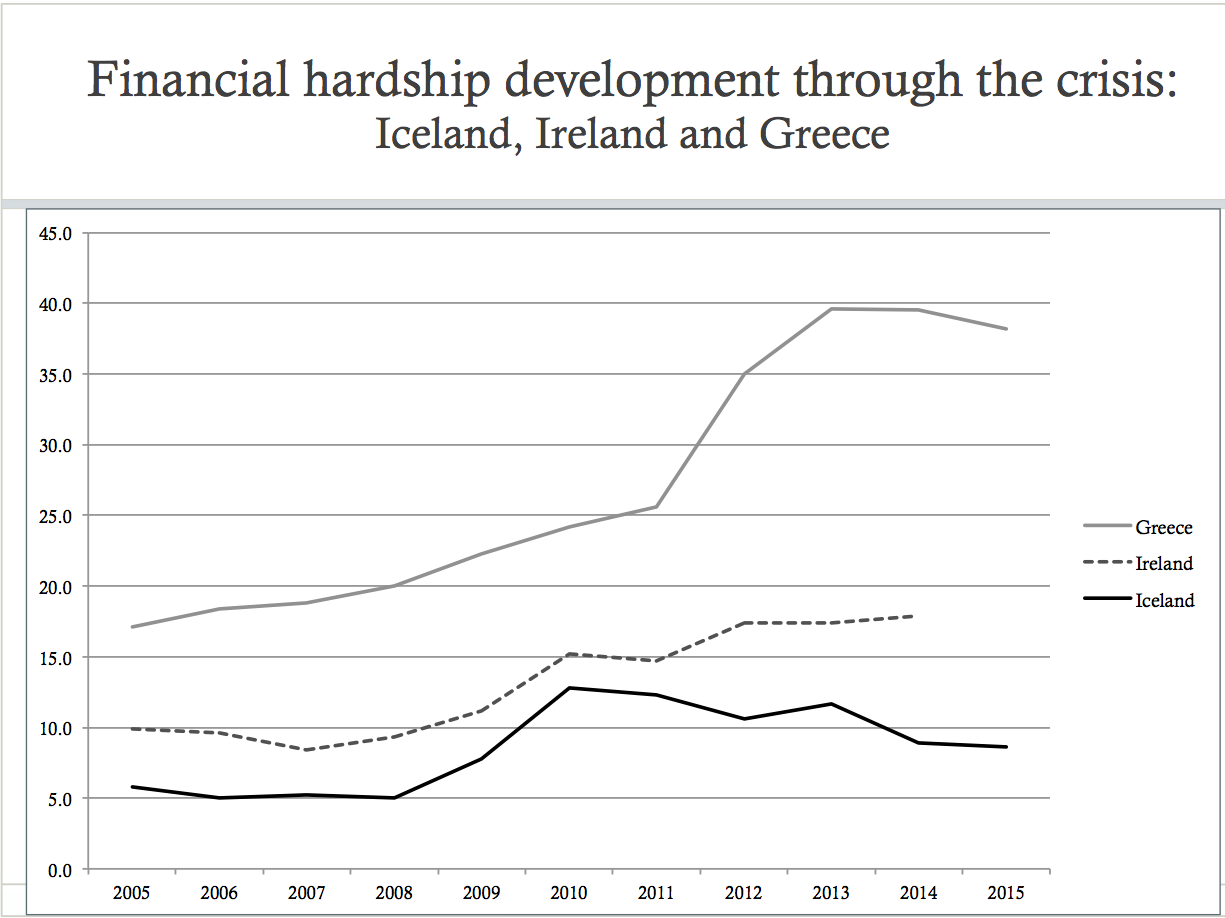

How the crisis developed

The crisis developed differently in the three countries, as the illustration below shows. The steep curve for Iceland shows how the country was hit immediately, but is now well on its way out of its problems. It is also worth highlighting that Iceland in 2014 had the lowest number of households below the poverty line out of all the countries in Europe.

Iceland did better than other countries which were severely hit by the crisis, and avoided large consequences for household welfare and emerged quicker out of the crisis, says professor Stefán Ólafsson.

From the data available, he concludes that the deeper the crisis, the larger the consequences for welfare.

“A strong welfare state cushions the consequences. The government’s ability and desire to handle the crisis did the same.

“More focus on cuts is often seen in correlation with more negative consequences for lower income groups.

“Redistribution policies cushion the effects of a crisis.”

In Iceland, many factors came together.

“The welfare policy focused on protecting the most vulnerable, and was carried out in an efficient manner. We devalued the krona. This reduced the value of households’ income. At the same time the consequences of the government’s policies were cushioned for lower income groups while they were tougher for those with higher incomes because of the redistribution of taxes. All this had a great impact on employment levels. We managed to maintain a high employment level throughout the crisis because of the welfare policy, the redistribution policy, the active labour market policy and the devaluation. It has also helped the tourism industry.”

Read more about the programme Nordic Welfare Watch here

Also read: Are the Nordic welfare states prepared for crises?

- Three people with different roles in the analysis and development of Iceland's welfare policies:

-

Professor Stefán Ólafsson, Minister of Social Affairs Eygló Harðardóttir and senior advisor and member of the Committee of Senior Officials at the Nordic Council of Ministers Ingi Valur Jóhannsson.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook