Munch in the canteen – for Freia’s workers only the best was good enough

Edvard Munch’s iconic The Scream created art history when it was sold at Sotheby’s in New York in 2012 for €91,033,826. The Scream is also part of the Anniversary Exhibition Munch 150, because Munch didn’t paint just one, but often several pictures of the same motif. The anniversary also features the Freia Frieze, which Munch painted for the workers’ canteen at the Freia chocolate factory in Oslo.

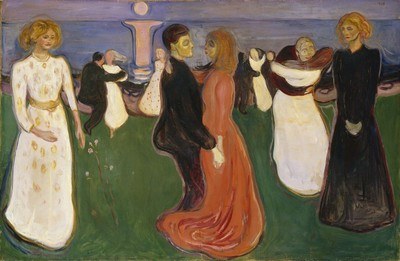

Munch liked to create stories through his pictures, writes Mai Britt Guleng in the catalogue Edvard Munch 1863-1944. She quotes Munch when he described the content of his Frieze of Life series:

“The frieze has been conceived as a series of decorative pictures that together are to give an image of life. Running through them winds the curving seashore, beyond which is the sea that is constantly in motion, and under the tree-tops life in all its diverse forms is lived, with all its joys and sorrows.”

The Dance of Life was one of the pictures in the series ‘Exhibition of a series of life pictures’ exhibited in Berlin in 1902. There was not only one frieze of life or motif, according to Mai Britt Guleng.

The number of artworks varied from six to 22. Not one single picture was part of all of the ten to twelve series he exhibited between 1893 and 1918, and only a handful of motifs were always represented: The Kiss, Madonna, Vampire, Melancholy, The Scream. But they were painted at different times with large variations in artistic idiom and to a certain extent composition.

There are several series which separately made up their own picture story, writes Guleng, who also says that during several phases Munch was working with concrete plans of a permanent life frieze. During the Anniversary Exhibition at the National Museum one variant of Munch’s frieze of life is exhibited in the same way as in Leipzig in 1903.

From the opening of the Anniversary Exhibition Munch 150. Left to right: Oslo Commissioner for Culture and Industry Hallstein Bjercke, Minster of Culture Hadia Tajik and directors Audun Eckhoff and Stein Olav Henrichsen

“The aim with the Anniversary Exhibition Munch 150 and the catalogue Edvard Munch 1863-1944 is to provide a presentation of Edvard Munch’s art and artistry which is as comprehensive and overarching as possible,” says Audun Eckhoff and Stein Olav Henrichsen, the directors of the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design and of the Munch Museum.

The exhibition features 170 artworks in chronological order and it covers his entire artistic life through 60 years. The National Museum shows highlights from his debut in 1883 until 1904, while the Munch Museum presents artworks from 1904 until his death in 1944.

The Freia Frieze hangs in the Freia hall at the chocolate factory which is now called Mondelez Norge, and it is open to the public at weekends.

Some of the highlights, in addition to the Frieze of Life, include the Linde Frieze with pictures like Dance on the Shore from 1904, the Reinhardt Frieze which was painted in 1906 and 1907 on commission from stage director Max Reinhardt who ran Deutsches Theater in Berlin from 1905 to 1933, and the Freia Frieze. The Workers Frieze which Munch wanted to paint never made it off the drawing board, but several expressive workers pictures contribute to the exhibition’s breadth.

Munch inspired work engagement

It is almost 100 years since the owner of the Freia chocolate factory in Oslo, Johan Throne Holst, commissioned Edvard Munch to paint 12 wall paintings for the women’s canteen. This became the picture story the Freia Frieze.

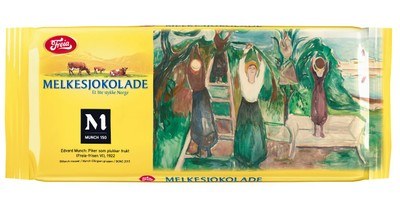

In the Munch 150 anniversary exhibition catalogue Patricia G. Bermann writes that “the Freia pictures appear – just like the Reinhardt Frieze, like a dream in an urban setting. As is fitting for a women’s canteen the main characters in the compositions are also women, watering plants, harvesting fruit, waving to the boats or contemplating by the water’s edge.”

In the biography of the chocolate king, Erik Rudeng quotes art critic Jappe Nilsen who wrote about the unveiling of the Freia pictures in the autumn of 1922: ”Freia has made a great undertaking. It has spearheaded development. It decided that for the workers only the best was good enough and has therefore got Norway’s greatest painter to decorate their canteen.”

”How do the workers show their gratitude?” Throne Holst was asked..

He felt that was the wrong way of putting the question. In an article printed in Sociale Meddelelser Throne Holst wrote:

”That is not the way in which the industry can see the fruits of such labour, no, that can be seen in the pure contentment and work engagement – despite pronounced dissatisfaction with things in general – which makes the workers perform better work, which on the other hand also brings the best workers to the business in question.”

The transformative power of art

In the catalogue Edvard Munch 1863-1944, Patricia G. Bermann also refers to a publication from 1955 where Alf Rolfsen writes how Throne Holst had recognised the transformative power of art:

"Art is not really understood; it is experienced (…) it helps us become alive. (…)” Throne wanted the best of Norwegian art for his two welfare areas, the canteen and the garden: Munch and Vigeland.

”The two company welfare areas express the will to give something back to the people which the machine has taken from them. For it is more than a play on words, that the more rational the industry the further it removes the people from the irrational. But art is a conveyor of the irrational, without which the human cannot continue being human.”

Johan Throne Holst made the Freia chocolate factory a pioneering company in terms of the work environment, and he was also an outstanding advertising man who used new tools. Polar explorer Roald Amundsen, one of the heroes of the time, was given Freia chocolate to snack on for his Antarctic expedition. In 1909 Norway’s first electric light advertising board shone down on the main Karl Johan Street in Oslo, and the chocolate boys at the National Theatre sold Freia chocolate.

Mondelez Norge has also tried their hand at PR stunts. Four of the motifs from Munch’s Freia Frieze are being used as illustrations for Freia Melkesjokolade (milk chocolate). The motif is women harvesting fruit.

The 12 wall paintings commissioned by Johan Throne Holst for the Freia chocolate factory’s 25th anniversary in 1923 cost 80,000 kroner, or just over 10,000 euro,

In the biography The Chocolate King, Erik Rudeng describes how Johan Throne Holst, in addition to commissioning works from the most famous painter of his time, also established a park for his staff with sculptures by famous artists like Gustav Vigeland. In 1914 he established the country’s first allotments for workers. 20 years before anyone else he hired the country’s first occupational doctor and created the foundation for Norway’s occupational health service. He introduced a 48 hour week before this was written into law in 1919.

Munch’s unfinished frieze

The idea for a series of pictures about workers was long part of Edvard Munch’s world of ideas, including as a proposal for the decoration of Oslo city hall.

Munch didn’t win that commission, but still painted some monumental pictures like ‘Workers on Their Way Home’.

‘Workers on Their Way Home’ (1913). One of Edvard Munch’ monumental paintings of workers from the Anniversary Exhibition ‘Munch 150’

The rest of the pictures planned as a series, or a frieze, never became more than sketches, says Gerd Woll, the leading expert on Munch’s workers pictures and a former Munch Museum curator. She would have loved to have seen more of the monumental workers pictures at Munch 150.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook