Robot journalism pushes the boundaries for what’s possible

Robots are taking over tasks only humans used to master, like writing articles and taking pictures. They relentlessly gather information or photograph the same subject hundreds of times.

Recently an article about an earthquake was published extremely quickly after the event in the online version of Los Angeles Times, thanks to the writer’s use of a robot to process information about the event.

This does not impress Sverker Johansson. He has written eight to nine percent of all Wikipedia entries - and we’re not talking about the Swedish language edition, but all Wikipedia entries.

“I reckon I have written more entries than anyone else in the world,” he says.

Sverker Johansson introduces himself in his own Wikipedia entry (above). But most people would have encountered his computer robot, or bot as they are known. Lsjbot, as he calls it, can select text and pictures from different catalogues and turn them into an entry.

A randomly chosen entry can look like this:

Thacanophrys goldsboroughi is a crustacean first described by Rathbun in 1906. Thacanophrys goldsboroughi is part of the Thacanophrys genus, and the Majidae family of crabs. There are no listed sub species.

There are source references and a fact box for how the crustacean fits in taxonomically. If you go to “behind” Wikipedia by clicking Show history, you will see that the article has been read three times in the past 30 days, and that three other bots have been making minor changes to the entry.

“Many of the entries are rarely read, but when I look at the statistics they are still read from time to time. Entries on birds are read more than those on bugs. But the day an insect becomes interesting, we’re ready,” he says.

Over six years with Wikipedia

Sverker Johansson is a trained physicist and linguist. He is the Director of Education and Research at the Dalarna University. For more than six years now, Wikipedia has been his main extra-curricular interest. He is one of several hundred Swedish Wikipedia administrators and is tasked with closing down those who are just messing about or who try to promote a certain point of view.

“I got the idea when I saw someone had done a similar thing on the Dutch Wikipedia. I thought I could do the same thing - only better."

“I knew how to write code, but not how to program bots. I was forced to learn this. Also I know enough about biology to understand how species databases are constructed.”

Cebuano and Waray-waray

He has published the more in-depth articles simultaneously in Swedish and the more unusual languages Cebuano and Waray-waray.

“My wife is from the Philippines and Cebuano is her native language. Waray-waray is spoken in some of the eastern provinces.”

He has also written entries on 1,000 Philippine municipalities, of course with the help of Lsjbot.

“My entries on the municipalities were useful during a recent natural disaster. A small village was washed away, and there was an entry about it.”

It took ten years for the Swedish language Wikipedia to go from zero to 500,000 entries. Then Sverker Johansson published one million entries in one go. This prompted some debate and there is still controversy surrounding bot-written entries.

“Many feel professional joy and pride in doing everything by hand. My texts are thin and not great literature. There is a certain margin of error and mistakes can be made during programming. But when it comes to errors, the bot texts do well compared to other written entries.”

90 percent computer generated?

The US company Narrative Science has specialised in computer generated articles on companies and sport. A finance publication like Forbes only has enough staff to write quarterly reports on 50 of the 500 largest companies. Narrative Science writes about the remaining 450 - and do it in four seconds rather than 40 minutes per company. According to the company’s CTO Kristian Hammond, 90 percent of news will be computer generated in 15 years time.

“In terms of volume it’s possible to have 90 percent of texts written by bots. But this will not apply to the texts we really read and re-read. It is the remaining 10 percent that count,” says Sverker Johansson.

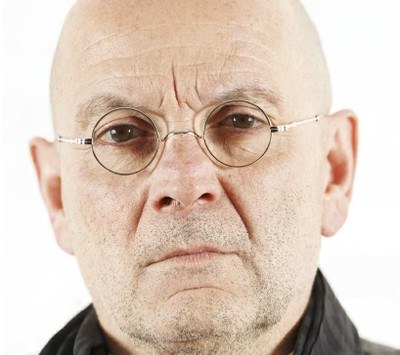

While both Sverker Johansson and Narrative Science write a little about a lot, the Swiss photographer Daniel Boschung uses an ABB robot to take extremely many pictures of the same subject. He makes portraits made up of 600 photographs of the same face. This makes it possible to study every little detail of the face.

“I have always looked for ways to create documentary photography using new technology. I then had a very serious mountain biking accident. Before they put screws in my spine which helped me walk again, they CT scanned me for half an hour to know exactly where to put the screws,” says Daniel Borschung.

During that process he got the idea to scan a face in the same way, nearly like mapping it.

“The tricky bit was not to get a robot to take 600 pictures with a depth of field of only one to three millimetres, but to put all of this together into one single image, taking into account the distortion created by moving the camera.“

Because the process can take up to half an hour, the resulting image is lacking in facial expression.

“The dialogue between the photographer and the sitter disappears. You’re left with a kind of very honest but at the same time upsetting portraits. Because of the perfect focus people believe it is a true picture, but at the same time the portrait is impossible,” says Daniel Borschung.

How would he describe his relationship with his robot? Is it part of him or an adversary who sometimes puts up resistance?

“For me it is a tool,” he says.

Sverker Johansson calls himself “the happy owner” of Lsjbot in his presentation, as if it were a pet. But he too describes the robot at a tool.

“There is a human being behind the written entry in any case. Different people use different tools to write.”

- Read more

-

about Daniel Boschungs robot photography here!

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook